Deadly Coral Disease Spreads Through Sand, Study Finds

Greag McFall/NOAAStony coral tissue disease kills a brain coral and infects the coral next to it in Florida's Looe Key.

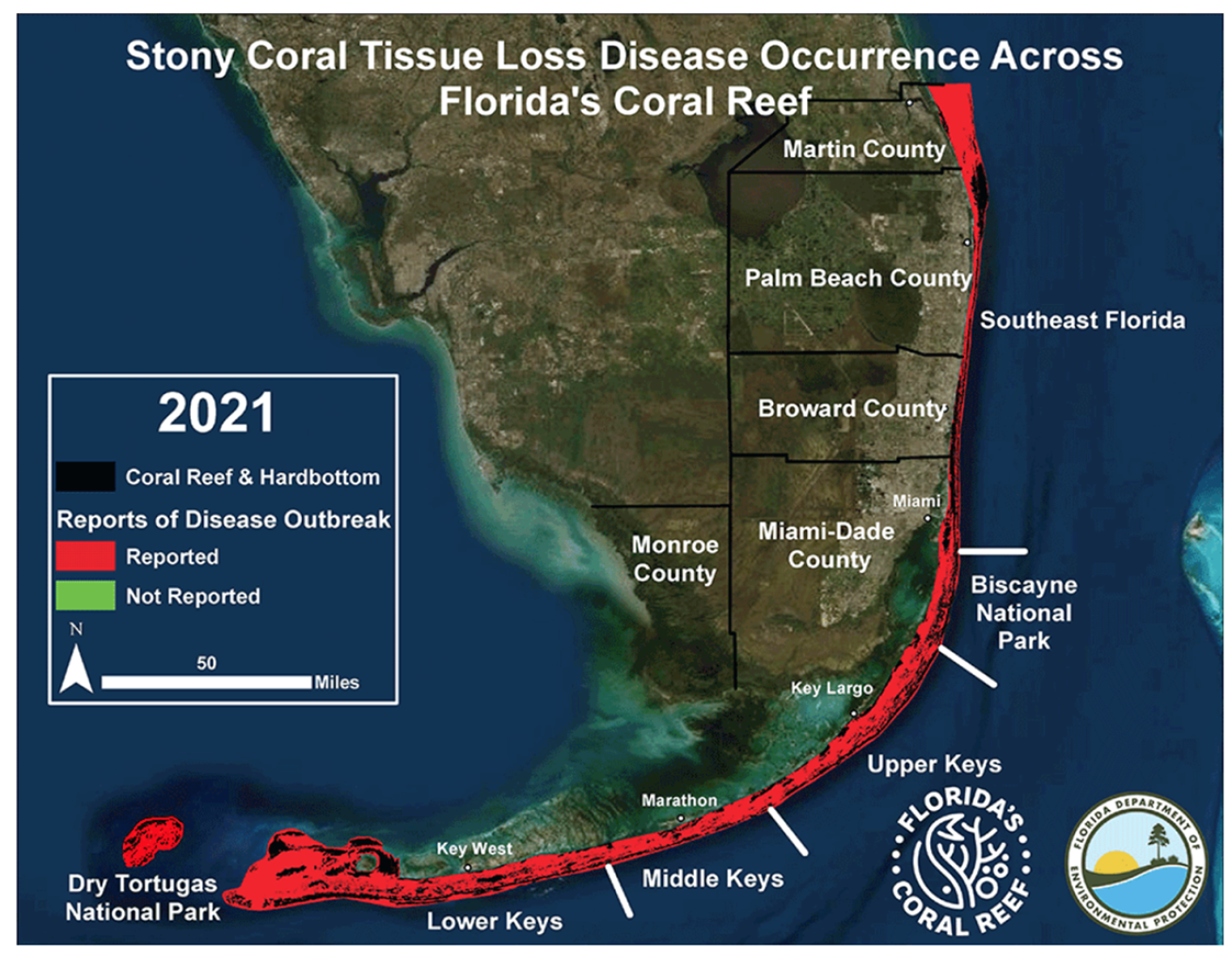

Sand at the bottom of the ocean can transmit stony coral tissue loss disease, which has killed millions of coral colonies, according to a new study. This finding could help mitigate transmission of the disease, which has spread throughout Florida and the Caribbean since 2014.

The disease’s origin is one of the “unanswered questions with this outbreak, and I'm not sure if we will ever really understand where it came from,” Michael Studivan, lead author of the study and a scientist at the University of Miami’s Cooperative Institute of Marine and Atmospheric Science, tells the Miami radio station WLRN. “But what this study tells us is that perhaps the disease can persist in these sediments, and so it needs to be something that we take into consideration going forward.”

Researchers placed uncontaminated corals in sediment that had been inoculated with the disease from infected corals. These initially healthy corals showed signs of disease about a day later.

“To see visible signs of lesion formation and bleaching after 24 hours was truly surprising,” says Studivan. “It emphasizes the potential for sediments to be a rapid way of moving the disease from coral to coral.” Previous research indicates it takes about two weeks for the disease to move from one coral to another.

NOAAThe disease was first spotted in Florida's Virginia Key in 2014. It has since spread throughout the region and the broader Caribbean.

Further analysis comparing diseased sediment to unaffected substrate revealed several known pathogens but did not identify a definitive cause. Corals interact with a host of ocean microbes, bacteria, viruses and fungi, which complicates determining a source.

“Corals are tricky animals, despite being considered very simple animals. In reality, they're often more complex than we give them credit,” Studivan says. “It becomes difficult to identify a specific pathogen.”

His team has shared its findings with the Florida Department of Environmental Protection and Army Corps of Engineers, which oversee coastal dredging and other activities that can cause large amounts of sediment to be stirred up or relocated.

"What we can do is try and manage how we move sediments, particularly for those larger projects, to ensure that we're not increasing the risk of transmission to a new area," he says. "If we've learned anything after seven years, it's that it's very difficult to pinpoint what's causing it. And so now we need to be focusing on what can we do to stop it.”