Ocean Health: How Scientists Measure It

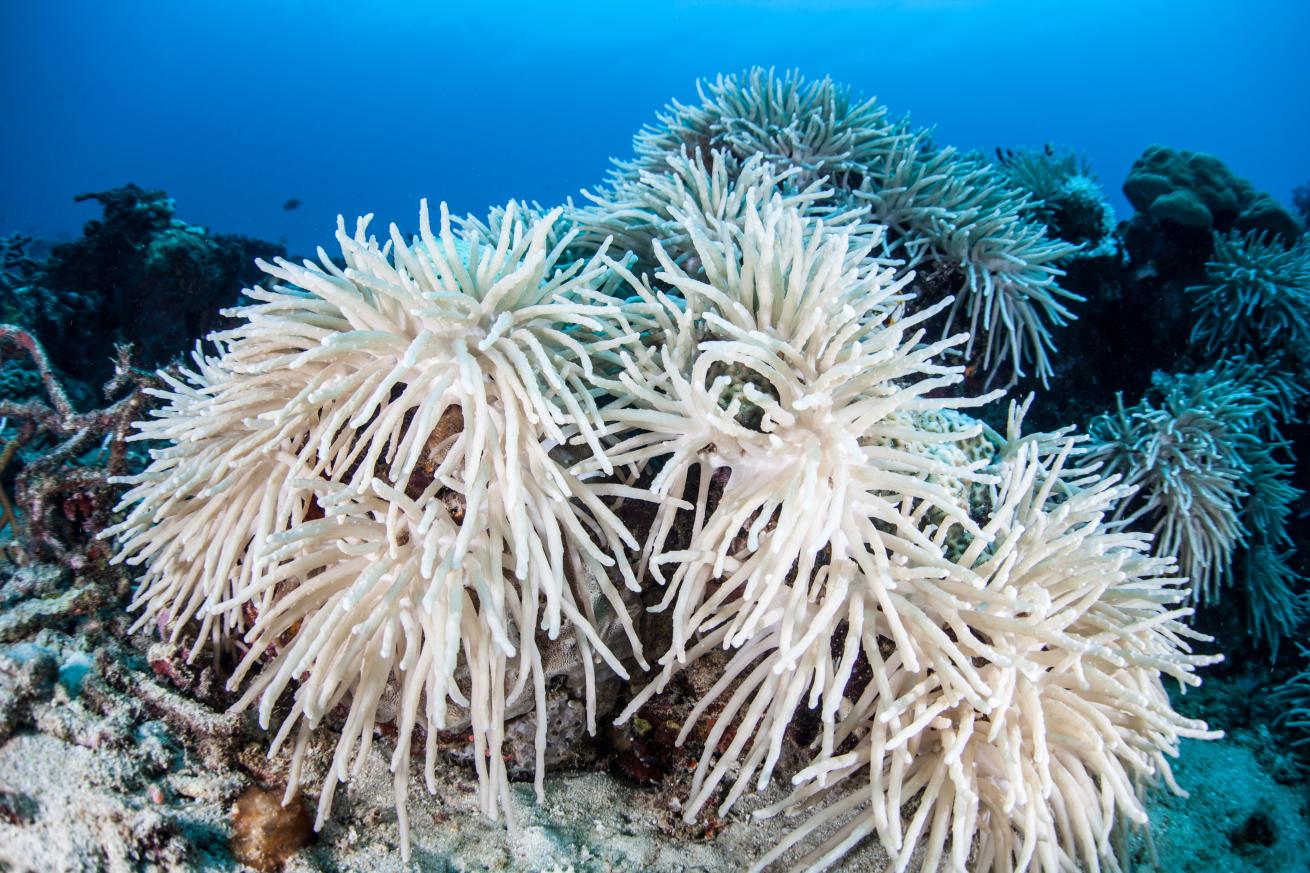

ShutterstockCoral bleaching represents a serious threat to reefs and is a sign that our oceans are in trouble.

We've seen signs as scuba divers — coral bleaching, marine mammals dying due to ingested plastic, outbreaks of nonendemic species. Most studies concentrate on one problem, in one specific area, such as evaluating the impact of invasive lionfish — Pterois volitans and Pterois miles — in the waters of a particular island, such as Little Cayman.

But is it possible to gauge the health of our oceans on a global scale? The scientists who work to create the Ocean Health Index since 2013 (planning began in 2008) use a number of tools to do just that. According to the OHI website, the index "is the first comprehensive global measurement of ocean health that includes people as part of the ocean ecosystem." In 2016, OHI scientists say there is no significant decline over the past year, “but the condition should not be mistaken as a clean bill of health.”

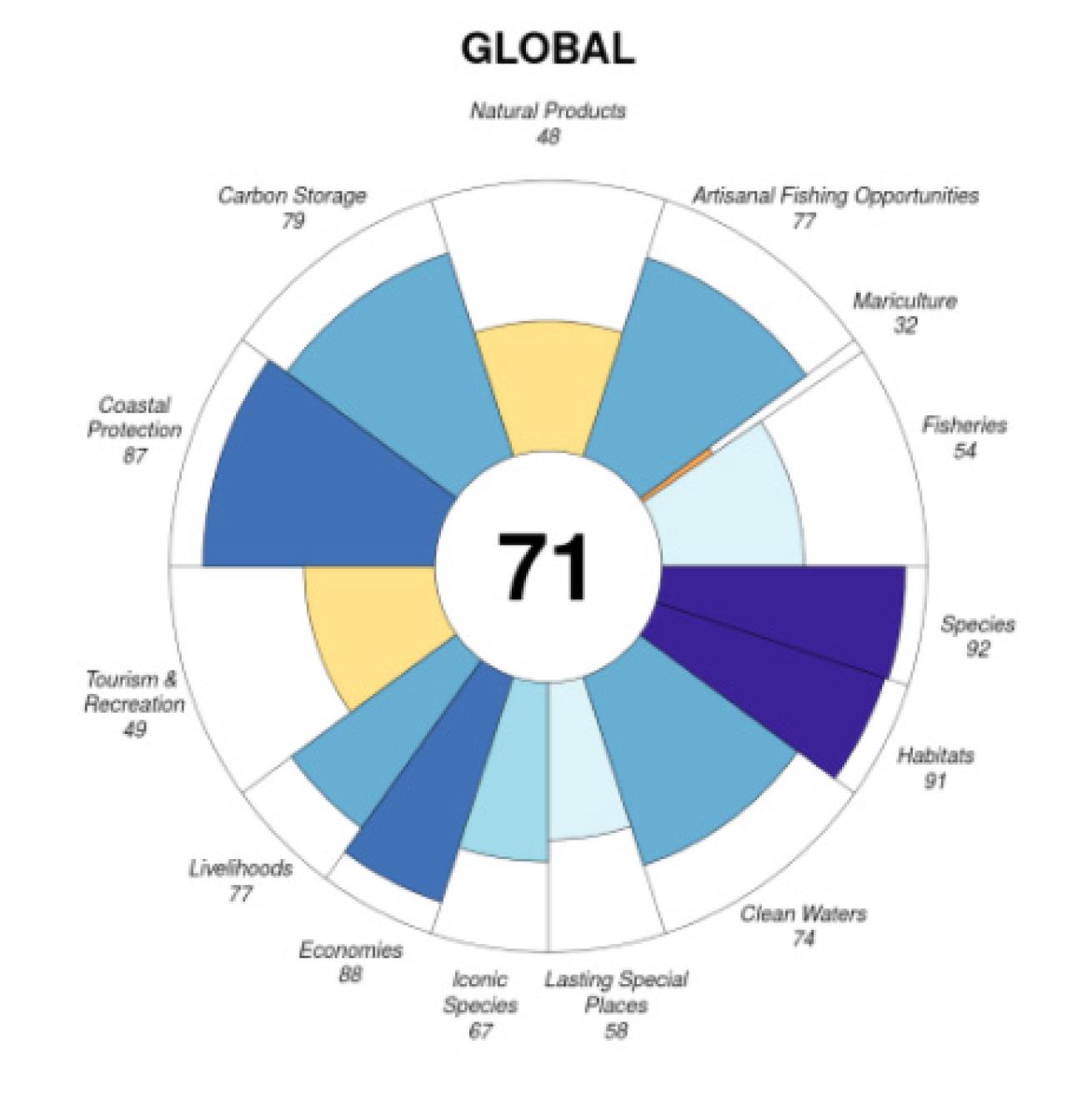

The OHI is designed to assess the benefits to people of healthy oceans; the OHI scientists evaluate the ecological, social, economic, and political conditions for every coastal country in the world. Their 2016 findings, published in the journal Nature, show that the global ocean scores 71 out of 100 overall on the Ocean Health Index, according to a press release from the University of California, Santa Barbara.

Courtesy Ocean Health Index2016 marks the fifth year of annual global Ocean Health Index (OHI) assessments, with scores representing ocean health for 220 coastal nations and territories using the best available data each year. Source: Halpern BS, Longo C, Hardy D, McLeod KL, Samhouri JF, Katona SK, et al. (2012) An index to assess the health and benefits of the global ocean. Nature. 2012;488: 615–620. doi:10.1038/nature11397

"Is the score far from perfect with ample room for improvement, or more than half way to perfect with plenty of reason to applaud success? I think it's both," said lead author Ben Halpern, an ecologist at UC Santa Barbara. "What the Index does is help us separate our gut feelings about good and bad from the measurement of what's happening. We’ve given the oceans their annual checkup and the results are mixed. It’s as if you went to the doctor and heard that, although you don’t have a terminal disease, you really need to change your diet, exercise a lot more and get those precancerous skin lesions removed. You’re glad you’re not going to die but you need to change your lifestyle.”

Established in 2012, the OHI is a partnership between UCSB's National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis (NCEAS) and the nonprofit environmental organization Conservation International. The index serves as a comprehensive tool for understanding, tracking and communicating in a holistic way the status of the ocean's health. It also provides a basis for identifying and promoting the most effective actions for improved ocean management on subnational, national, regional and global scales.

Read our picks for the World’s Best Scuba Diving Destinations.

"Several years ago I led a project that mapped the cumulative impact of human activities on the world's ocean, which was essentially an ocean pristine-ness index," said Halpern, who is a researcher at UCSB's National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis (NCEAS), as well as UCSB's Marine Science Institute. He also directs UCSB's Center for Marine Assessment and Planning. "That was and is a useful perspective to have, but it's not enough. We tend to forget that people are part of all ecosystems –– from the most remote deserts to the depths of the ocean. The Ocean Health Index is unique because it embraces people as part of the ocean ecosystem. So we're not just the problem, but a major part of the solution, too."

The authors of the Nature report readily acknowledge methodological challenges in calculating the Index, but emphasize that it represents a critical step forward. "We recognize the Index is a bit audacious," said Halpern. "With policy-makers and managers needing tools to actually measure ocean health –– and with no time to waste –– we felt it was audacious by necessity."

The OHI team works directly with more than 25 countries across priority marine regions, including the Pacific, East Africa and Southeast Asia. Nations in these areas lead independent assessments known as the OHI+, which have already driven marine conservation actions at national levels by shaping China’s 13th five-year plan, Ecuador’s National Plan for Good Living and Mexico’s National Policy on Seas and Coasts.