Ocean Planet: Saving Cocos' Sharks and Turtles

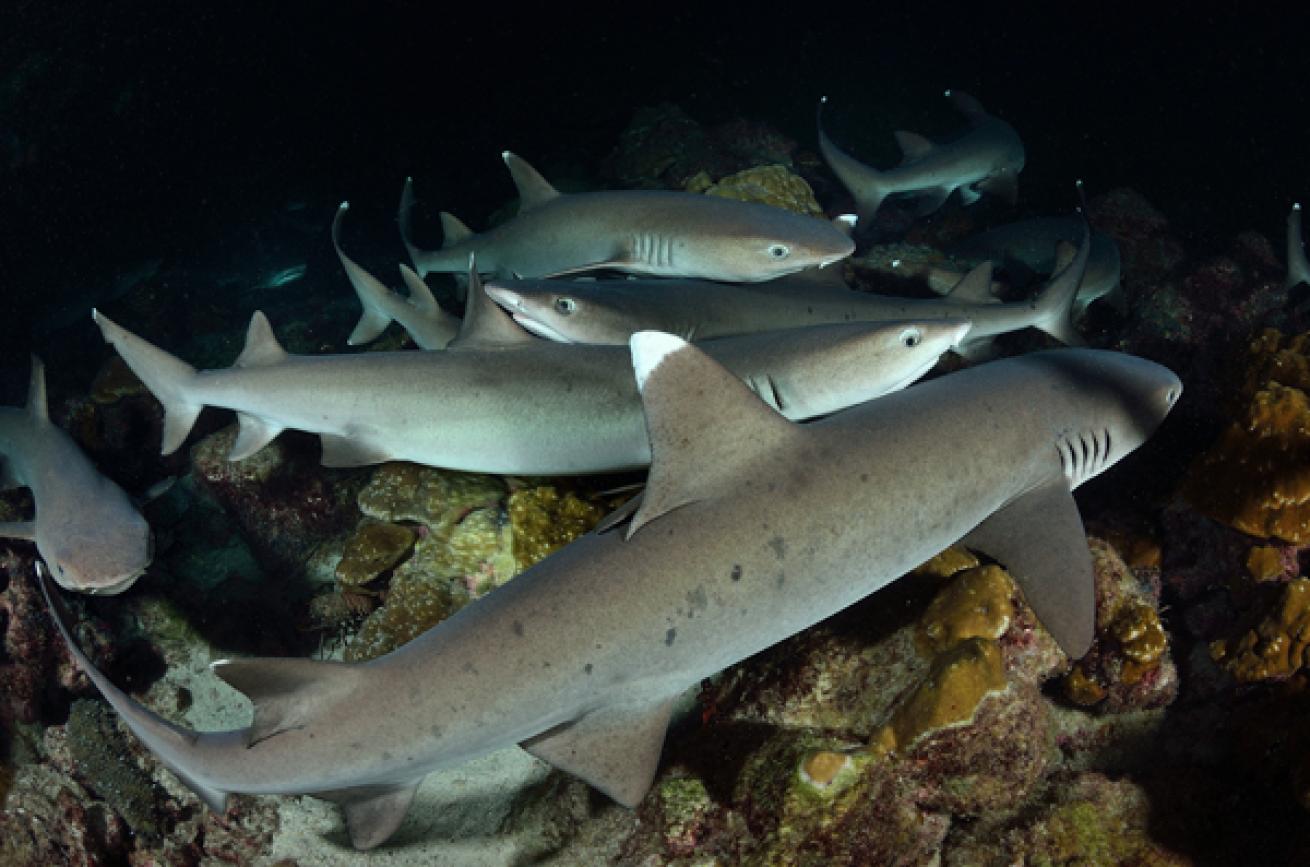

Divers from around the world are drawn to Costa Rica’s Cocos Island as if on a pilgrimage, to dive at the heart of one of the largest concentrations of sharks and pelagic species in the world.

This teeming biodiversity hot spot — an uninhabited desert island 340 miles off the Pacific coast — is the product of marine corridors between Cocos, Malpelo Island of Colombia and the Galapagos Archipelago of Ecuador. This “Golden Triangle” forms a breeding ground that allows for healthy populations of sharks, sea turtles and other species.

The islands are marine sanctuaries under the protection of UNESCO; the migratory corridors between them are not. They are at the mercy of longline fishermen who practice an unspeakable type of fishing: shark finning. Sea turtles also fall victim to their longlines. And Costa Rica lacks the resources to adequately staff and fund the protections already in place.

In 2004, environmental activists Randall Arauz, founder of the grass-roots advocacy group Pretoma (pretoma.org), and Todd Steiner, founder of the Sea Turtle Restoration Project (seaturtles.org), were outraged by the barbarism of many unsustainable fishing methods. They decided to start tagging hammerhead sharks and sea turtles near Cocos — with the aid of data gathered, they hoped to persuade the governments concerned to protect these areas and species that are on the path to extinction.

“My career took a serious turn when I met Todd,” Arauz recalls. “He taught me to be an activist.”

I arrange to accompany the pair on a Cocos trip devoted to tagging hammerhead sharks and sea turtles. They have brought the equipment necessary to record the movements of the animals — two types of beacons: satellite and acoustic. The former are used for sea turtles. Captured by hand then brought on board, they are measured, weighed and fitted with a satellite beacon before being put back into the water. These receivers then track them, almost in real time, when they surface to breathe.

For hammerheads, which spend most of their time at the bottom of the ocean, acoustic beacons are needed. It is not easy to tag them. Very meticulously, we use underwater tag poles and place a dart tag under the shark’s skin, to which a beacon is attached. Then, using underwater receivers at various locations around the island, scientists can detect and record the frequency of the shark’s passing. These receivers are replaced during each new expedition by Arauz, Steiner and their team of volunteers. To supplement the data, similar receivers have been installed around the Galapagos, Malpelo and along the coast of Costa Rica.

“Since 2004, we have tagged over 90 sharks with acoustic tags, caught over 80 turtles and tagged 18 so far with satellite and acoustic tags,” says Arauz.

The data gathered establishes that the tagged animals are not endemic to one island or area in particular. Quite the opposite, they move seasonally and travel thousands of miles each year between the islands of the Golden Triangle. It is therefore absolutely necessary to protect these islands, and the underwater highways that connect them. Despite a zone of 20 nautical miles around the island — where all fishing is prohibited — fishermen lay lines with thousands of hooks at the edge of the protected zone. Then they wait for strong Pacific currents to pull the lines into the waters of the marine park, lines they haul in under the cover of darkness. Their ships can be seen, out at sea, lying in wait.

The few park rangers present on the island, despite their determination, are helpless to stop it. Due to a lack of means and manpower, they can cover the zone only a few hours a week in their small boats. One of the rangers tells us that even within the park, populations of sharks and pelagic species have diminished by 70 percent in 10 years — this at the heart of a sanctuary classified as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO.

Let’s not be naive. When longline fishermen are forced to come and fish here at Cocos, it’s because the fish, the pelagic species and the sharks have become scarce along the continental coasts. Cocos, like the Galapagos, is among the last places on this planet where we can still see the richness and abundance of marine life as it must have been several centuries ago. We must act before we’ve reached the point of no return, or the struggle undertaken by Arauz and Steiner will be in vain.

In October of last year, Costa Rica’s president Laura Chinchilla signed a law prohibiting all forms of shark finning along the coasts of Costa Rica — a first step.

“Stopping the shark finning is great,” Arauz says, “but we are at a point now where there are so few sharks that we have to start talking about reducing shark mortality. We need to reduce fishing pressures.”

It is up to all of us to create the opportunity for more steps to be taken.

How You Can Help

1 Get involved with the work of pretoma.org and seaturtles.org.

**2 **Lend your support to organizations working for a ban on international trafficking of sharks.

3 Don’t consume sharks of any sort or products derived from sharks.

**4 **Work to sensitize your family, friends, neighbors and politicians to the plights of sharks.

Damien MauricTodd Steiner (left) and Randall Arauz (right) fit satellite tracking beacons to a Cocos turtle.

Damien MauricCocos' abundant sharks are threatened by illegal longlining.

Divers from around the world are drawn to Costa Rica’s Cocos Island as if on a pilgrimage, to dive at the heart of one of the largest concentrations of sharks and pelagic species in the world.

This teeming biodiversity hot spot — an uninhabited desert island 340 miles off the Pacific coast — is the product of marine corridors between Cocos, Malpelo Island of Colombia and the Galapagos Archipelago of Ecuador. This “Golden Triangle” forms a breeding ground that allows for healthy populations of sharks, sea turtles and other species.

The islands are marine sanctuaries under the protection of UNESCO; the migratory corridors between them are not. They are at the mercy of longline fishermen who practice an unspeakable type of fishing: shark finning. Sea turtles also fall victim to their longlines. And Costa Rica lacks the resources to adequately staff and fund the protections already in place.

In 2004, environmental activists Randall Arauz, founder of the grass-roots advocacy group Pretoma (pretoma.org), and Todd Steiner, founder of the Sea Turtle Restoration Project (seaturtles.org), were outraged by the barbarism of many unsustainable fishing methods. They decided to start tagging hammerhead sharks and sea turtles near Cocos — with the aid of data gathered, they hoped to persuade the governments concerned to protect these areas and species that are on the path to extinction.

“My career took a serious turn when I met Todd,” Arauz recalls. “He taught me to be an activist.”

I arrange to accompany the pair on a Cocos trip devoted to tagging hammerhead sharks and sea turtles. They have brought the equipment necessary to record the movements of the animals — two types of beacons: satellite and acoustic. The former are used for sea turtles. Captured by hand then brought on board, they are measured, weighed and fitted with a satellite beacon before being put back into the water. These receivers then track them, almost in real time, when they surface to breathe.

For hammerheads, which spend most of their time at the bottom of the ocean, acoustic beacons are needed. It is not easy to tag them. Very meticulously, we use underwater tag poles and place a dart tag under the shark’s skin, to which a beacon is attached. Then, using underwater receivers at various locations around the island, scientists can detect and record the frequency of the shark’s passing. These receivers are replaced during each new expedition by Arauz, Steiner and their team of volunteers. To supplement the data, similar receivers have been installed around the Galapagos, Malpelo and along the coast of Costa Rica.

“Since 2004, we have tagged over 90 sharks with acoustic tags, caught over 80 turtles and tagged 18 so far with satellite and acoustic tags,” says Arauz.

The data gathered establishes that the tagged animals are not endemic to one island or area in particular. Quite the opposite, they move seasonally and travel thousands of miles each year between the islands of the Golden Triangle. It is therefore absolutely necessary to protect these islands, and the underwater highways that connect them. Despite a zone of 20 nautical miles around the island — where all fishing is prohibited — fishermen lay lines with thousands of hooks at the edge of the protected zone. Then they wait for strong Pacific currents to pull the lines into the waters of the marine park, lines they haul in under the cover of darkness. Their ships can be seen, out at sea, lying in wait.

The few park rangers present on the island, despite their determination, are helpless to stop it. Due to a lack of means and manpower, they can cover the zone only a few hours a week in their small boats. One of the rangers tells us that even within the park, populations of sharks and pelagic species have diminished by 70 percent in 10 years — this at the heart of a sanctuary classified as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO.

Let’s not be naive. When longline fishermen are forced to come and fish here at Cocos, it’s because the fish, the pelagic species and the sharks have become scarce along the continental coasts. Cocos, like the Galapagos, is among the last places on this planet where we can still see the richness and abundance of marine life as it must have been several centuries ago. We must act before we’ve reached the point of no return, or the struggle undertaken by Arauz and Steiner will be in vain.

In October of last year, Costa Rica’s president Laura Chinchilla signed a law prohibiting all forms of shark finning along the coasts of Costa Rica — a first step.

“Stopping the shark finning is great,” Arauz says, “but we are at a point now where there are so few sharks that we have to start talking about reducing shark mortality. We need to reduce fishing pressures.”

It is up to all of us to create the opportunity for more steps to be taken.

How You Can Help

1 Get involved with the work of pretoma.org and seaturtles.org.

**2 **Lend your support to organizations working for a ban on international trafficking of sharks.

3 Don’t consume sharks of any sort or products derived from sharks.

**4 **Work to sensitize your family, friends, neighbors and politicians to the plights of sharks.