The Ugly Face of Bycatch

Brian RaymondAfter seeing and documenting countless dead dolphins and shark pups as a commercial fisherman, Brian Raymond now opts to shoot photos of sharks as a shark diving operator in Rhode Island.

Sifting through archived images in his Rhode Island home, Brian Raymond stumbled upon a series of disturbing photographs. So much has changed since his days as a commercial fisherman; yet, as he scrolled through the images, a range of emotions came flooding back.

Raymond was born into a family of fishermen—and for a while, it was all he knew. For the better part of a decade, he worked on a commercial fishing vessel off New England. Most days were spent at sea hunting squid.

“Growing up in a fishing family, it was always about discovery and adventure on the water, but the reality of the industry is much different than the way I remembered it,” Raymond says.

During his time as a fisherman, his boat regularly hauled in nontargeted species—also known as bycatch. Large pelagics such as dolphins and sharks were often caught and killed accidentally and brought on board alongside the targeted catch. It happened so frequently that through the years, Raymond became somewhat desensitized to it—much in the same way many people drive past roadkill without a second thought.

Brian Raymond“Being able to experience sharks in their own environment, seeing them for what they really were, brought all of those feelings flooding back, and I knew that this was what I desired, and not fishing.”

Sadly, the majority of the world’s bycatch goes unreported, posing a major threat to maintaining healthy ecosystems. While the data is hard to obtain and verify, some reports estimate that bycatch makes up 40 percent of the world’s catch, resulting in many of these species dying or being thrown back with injuries. Hundreds of thousands of small whales, dolphins, sharks, turtles and seabirds lose their lives each year to help satisfy our insatiable demand for seafood.

Yet many tend to think of issues such as bycatch and overfishing as something that doesn’t impact their local community —but rather an issue far out at sea, in some remote corner of the world. With 38 million tons of unintentional species caught each year, one can come to their own conclusions on its level of sustainability. While the practices may or may not be local, the net impact on our global ecosystem hits us right at home wherever we reside.

Brian Raymond“Growing up in a fishing family, it was always about discovery and adventure on the water, but the reality of the industry is much different than the way I remembered it”

Raymond says fishermen do not target or relish the accidental mortalities, but they have become desensitized to the process in their quest to put food on their own tables.

In the United States, NOAA implements the Observer Program, which essentially strives to monitor fisheries and fish populations via independent contractors. The data collected by observers is compiled into reports that help set fishing quotas and other rules, but Raymond believes that while “the goal of the program is a good one, [the] lack of coverage by observers and transparency by the fishermen make that difficult.”

Up until recently, observers were the only independent third party tasked with validating catch information on federally licensed fishing vessels. But the days of manual reporting and costly observers are slowly being replaced by new technology. In New England, an electronic monitoring pilot project is currently underway to collect the most accurate information possible.

Can We Save the Hammerhead Sharks of Cocos, Galapagos and Malpelo?

To date, roughly two-dozen fishing vessels have voluntarily installed on-board cameras. The hope is that much of the uncertainty surrounding catch estimates will finally be put to rest, and that this data will encourage the reduction of discard and bycatch. The trend is slow, however, as only a thousand fishing vessels around the world currently use electronic monitoring.

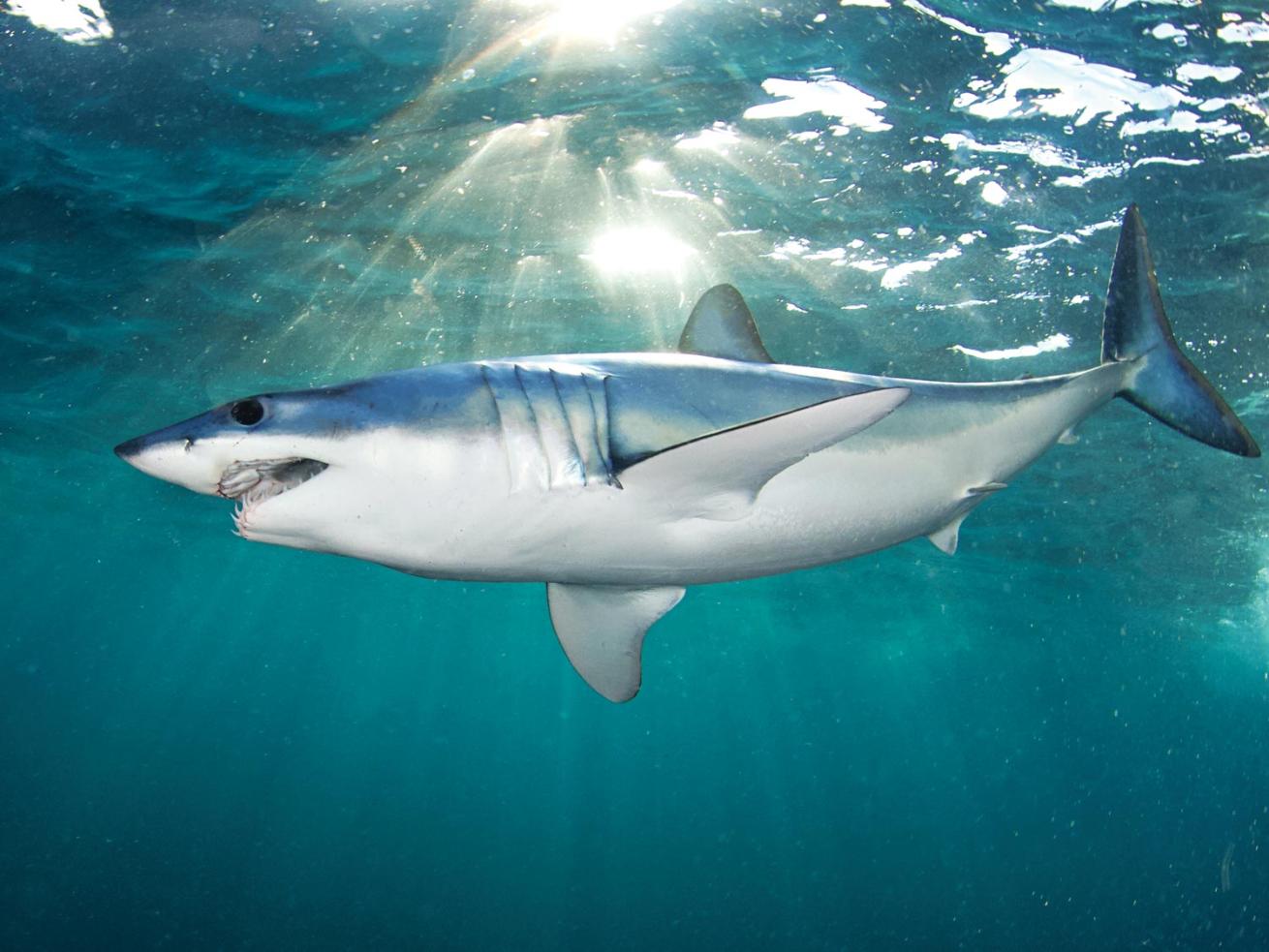

Brian RaymondBycatch claims this porbeagle—a species of mackerel shark—as a victim.

Other promising technologies, such as the NOAA project EcoCast, are being utilized to help fishermen find their targeted catch, but at the same time providing up-to-date information on areas where tagged, protected marine life is found. Although much discretion is placed in the hands of those who have a financial interest in a school of fish that might be within the animals’ vicinity, it’s intended as a step in the right direction. With more awareness, transparency and new technology, bycatch eventually might decrease—but how much damage will have been done before we reach that point?

As time passed, Raymond chose to leave behind commercial fishing for a more sustainable business: Rhode Island Shark Diving.

“Being able to experience sharks in their own environment, seeing them for what they really were, brought all of those feelings flooding back, and I knew that this was what I desired, and not fishing,” Raymond says. “It changed my life.”

While the bycatch images remained on his hard drives, they were even more permanently ingrained in his mind. That evening, as he dusted off his drives, Raymond knew it was time to reveal the pictures. One by one, he shared the images on social media. But the outcry and sheer shock surprised him. Raymond appreciates that his bycatch images are disturbing; however, he knows firsthand that the realities remain far worse.