Why You Shouldn’t Feed Lionfish to Sharks

Shutterstock.com/Ye Choh WahDubbed “the Hoover vacuums of the sea” for their voracious and undiscriminating appetites, lionfish were first detected in the Caribbean in the mid-1980s.

A diver cruised along, holding her spear tightly after a successful dive in Placencia, Belize. Suddenly, her right arm felt like it had been hit by a brick. She looked down, shocked to see a nurse shark latched onto her hand.

Why would such a placid animal attack without provocation? Earlier that morning the diver had been culling lionfish. The scent of the kill lingered on her spearhead, attracting the inquisitive shark.

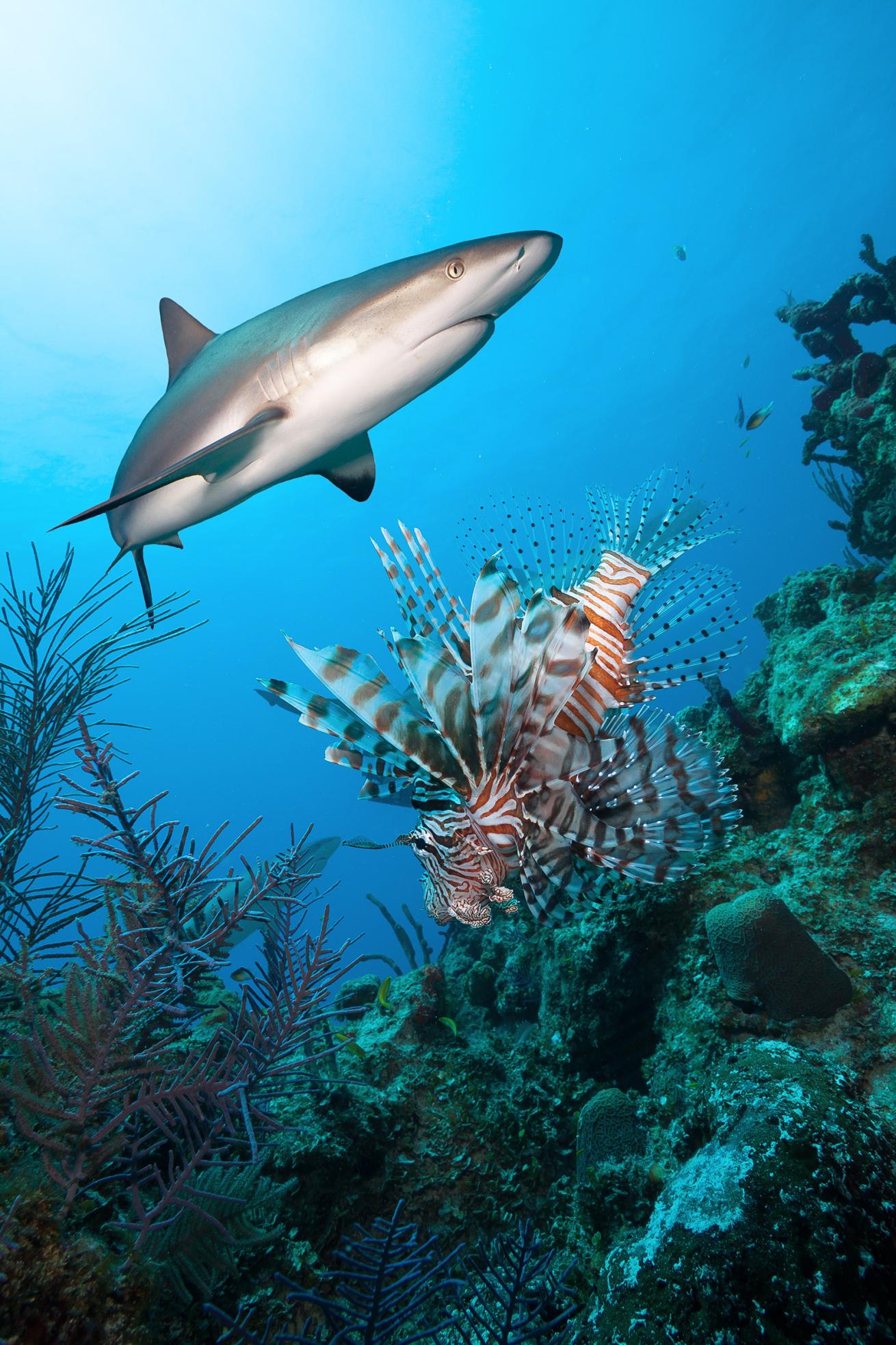

If you’ve gone diving in the Caribbean, you’ve probably seen them. Flamboyantly beautiful and venomous, lionfish are an invasive species that—without their natural predators to keep them in check—has the potential to overrun vulnerable coral reef ecosystems outside the Indo-Pacific.

Dubbed “the Hoover vacuums of the sea” for their voracious and undiscriminating appetites, lionfish consume up to 460,000 small fish, eggs, crustaceans and mollusks per acre per year. Scientists have even discovered that a single lionfish can reduce native reef fish recruitment (the process by which very young fish mature) by 79%.

Fighting for a Solution

Divers in the Caribbean, Western Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico have been waging war on lionfish since they were first detected along Florida coasts in the mid-1980s, killing them one by one and fileting their lobster-like flesh to cull the out-of-control population. The problem: Female lionfish release 50,000 eggs every three days during their entire mature lifespan, and no one can eat that much ceviche.

In search of a long-term solution, some divers sought reinforcements by spearing lionfish and feeding them to large predators, such as sharks, moray eels and groupers, hoping to teach the animals that the spiny, intimidating fish are, in fact, delicious. Whether the campaign has been successful is up for debate.

One 2013 study conducted in Mexico, Belize, Honduras, Cuba and the Bahamas found that native predators do not influence the population density of invasive lionfish on Caribbean reefs.

Related Reading: Diving with—and Saving—North Carolina's Sand Tiger Sharks

Shutterstock.com/frantisekhojdyszPredation on Caribbean lionfish may be occuring, whether it was influenced by humans or not is still unknown.

However, newer anecdotal evidence exists that predation on Caribbean lionfish may be occurring—whether it was influenced by humans or not. Lionfish University co-founder Jim Hart filmed a Nassau grouper hunting and successfully eating a lionfish without any encouragement from a diver while in Little Cayman.

Meanwhile, Steve Gittings, chief scientist for NOAA’s Office of National Marine Sanctuaries and science advisor for Lionfish University, says that lionfish numbers seem to be past their peak in many areas.

“We’re trying to figure out why. It's possible that the lionfish are adjusting to changes in the abundance of prey or that predatory fish have figured out that they can eat them. We do hear from fishermen that they are finding lionfish in the stomachs of the fish they’ve caught.”

Unintended Consequences

One fact is certain: Spearing lionfish in the presence of animals like sharks and eels can be dangerous once it puts them into a heightened predatory mode. Harry Neal, a freelance PADI Divemaster based in Belize, has personally witnessed eels, nurse sharks and Caribbean reef sharks biting or attempting to bite divers who are on the hunt.

“We’ve noticed a problem with the nurse sharks and green morays in particular,” he says. “At certain dive sites, we start spearing lionfish and the scent disperses. So the predators are smelling it. But they’re not getting it. It’s like teasing. They can get wild and aggressive.”

Perhaps most concerning is that many of these intelligent predators have become habituated from intentional and unintentional feedings and now associate divers with food, following them closely and acting bolder than they would naturally. Neal, Hart and Gittings have all seen sharks and grouper point to hiding lionfish like “bird dogs,” hoping divers will hand them an easy meal.

Related Reading: How Captive Breeding is Helping Shark Conservation

“There was a lionfish culling program in Little Cayman that started in 2012,” says Hart. “That led to a definite change in behavior. By the time you got in the water and were down to depth to hunt for the lionfish, the reef sharks were already circling. They no longer let you spear when you’re out with recreational divers because of the liability.”

Neal says that at certain dive sites, the marine life has become so persistent that even people who aren’t spearing have to be more aware of their surroundings.

“It’s alarming,” he says. “We’ve taken a break from killing lionfish in particular areas.”

See a lionfish? Make sure to report the sighting via the Reef Environmental Education Foundation reporting app.

How to Hunt Lionfish Safely

Speak up. While many divemasters spear lionfish to help local reefs, some do it specifically to attract sharks and eels to make divers happy. If this happens to you, don’t be afraid to speak up and say you aren’t comfortable with feeding wildlife.

Contain your catch. When spearing lionfish yourself, don’t forget to bring a ZooKeeper or similar container to keep your caught lionfish away from predators.

Just drop it. Don’t hold onto your lionfish or container if your safety is at risk. “I've noticed that sometimes when people are getting attacked, they hang onto their ZooKeepers instead of just dropping them and coming back to get them later,” says Stacy Frank, co-founder of Lionfish University. Similarly, Neal suggests shaking dead lionfish off your spear if a predator appears interested. “It’s their world,” he says. “Once the predators decide they want what you have, they’re going to stay with you.” Distance yourself from aggressive animals as quickly as possible, and don’t hesitate to call the dive.

Don’t spear lionfish at dive sites with habituated animals. If you go to a new dive site to hunt lionfish and a shark or eel immediately starts following you, don’t spear anything. The marine life is likely too habituated for you to hunt safely.