British Columbia's Top 10 Dives

|

July 2001

Text and Photography by Neil McDaniel

With 17,000 miles of Pacific coastline, rich waters teeming with life and dive attractions as diverse as glacier-chiseled fjords and modern steel warships, it's little wonder that British Columbia earned the 2001 RSD Readers' Choice Award for Best Overall Dive Destination in North America.

But there's a catch. B.C.'s diving conditions are far more challenging than tropical destinations. The water is cold, the visibility sometimes limited and tidal currents can really cook. But for real divers looking for real adventure, these are all part of the fun. I was asked to name just 10 of the "best" sites--a difficult task that's sure to generate plenty of arguments among my fellow British Columbians, but hey, it's my top 10. Here they are, from south to north.

Race Rocks

These rugged islets lie off the southern tip of Vancouver Island and are the most southerly point in western Canada. Marked by a distinctive black and white lighthouse, they guard the entrance to the Strait of Juan de Fuca.

Dive Log: While the coast of B.C. boasts dozens of impressive dive sites, few match this combination of diverse invertebrate life, marine mammals and rugged topside scenery. Washed daily by chilly ocean water, the rocks support shallow forests of bull kelp, which in turn shelter juvenile rockfishes and armies of grazing sea urchins. Deeper, the underwater cliffs are emblazoned with a living carpet of softball-size barnacles, pastel brooding anemones, vivid lavender hydrocorals, pink soft corals and basket stars.

More than 1,000 California and Steller's sea lions congregate on the rocks in the fall and several hundred harbor seals live at the rocks year-round.

Heads Up: The entire area inside the 20-fathom (120-foot) contour line is an ecological reserve and there is a strict ?no-touch' policy. The area is swept by tidal currents of up to six knots and is exposed to winds from all quarters. Surge can be a concern, especially on west-facing shores exposed to ocean swells that pound the rocks. Visibility varies, but the autumn months offer a reliable 40 feet or more.

Renate's Reef

The west coast of Vancouver Island is stocked with everything from rock reefs to shipwrecks. This open-water pinnacle lies in Barkley Sound and consists of two distinct ridges that rise to within 30 feet of the surface.

Dive Log: The peaks of Renate's Reef are overgrown with massive yellow clumps of calcareous staghorn bryozoan, which gives the site an uncanny resemblance to a tropical coral reef. The reef is riddled with gullies, providing home to several approachable wolf eels. Scattered throughout are clusters of plumose, fish-eating and white-spotted anemones and all manner of colorful encrusting invertebrates. The variety of rockfish is exceptional; on a single dive one can spot china, black, blue, yellowtail, tiger, copper, quillback, vermilion, canary and even yelloweye rockfish.

Heads Up: Divers need to be especially careful not to blunder into the delicate hydrocoral colonies. Surge can sometimes be a concern here and heavy ocean swells can make the reef too dangerous to dive.

|

Porlier Pass

This current-swept channel separates Galiano and Valdes islands, and offers several remarkable sites. As tidal currents flow through the southern Strait of Georgia, they are forced through the many narrow channels that separate the Gulf Islands. The passages, including Dodd Narrows, Gabriola Pass, Porlier Pass, Sansum Narrows and Active Pass, are among the best dive sites in the Gulf Islands because the tidal currents deliver copious amounts of food to sessile marine creatures.

Dive Log: One of the gems in Porlier Pass is Boscowitz Rock, a kelp-fringed pinnacle that lies only a stone's throw off Race Point. The reef is loaded with marine life, including carpets of dahlia, plumose and brooding anemones, basket stars, blue-clawed lithode crabs and sprawling violet patches of encrusting hydrocorals.

Near the center of the pass on Virago Rock lie the battered remains of the steam tug Point Grey. It stranded on the then unmarked reef in 1949. A decade later a violent storm toppled the wreck onto a shallow ledge, where the fast currents soon transformed the steel skeleton into a living reef. The ship provides underwater photographers with excellent wide-angle opportunities. On autumn days, visibility is good enough to see more than half of its 105-foot length.

Heads Up: Porlier Pass is a heavily transited navigational passage. Beware boat traffic.

Flora Islet

This small islet lies off the easternmost tip of Hornby Island, a scenic Gulf Island lying about halfway along the east coast of Vancouver Island in the Strait of Georgia.

Dive Log: Flora Islet features a steep, terraced drop-off that plunges dramatically into depths well over 600 feet and offers the chance to swim with sixgill sharks. Nobody knows why these deep-water behemoths regularly venture into the shallows here, but this is your chance to swim with eight- to 14-foot-long sharks as they slowly cruise the wall, oblivious to the attentions of excited divers. The parade of sixgill sharks begins in the late spring and continues into the early autumn. During the summer months it is not uncommon to see two or three different sharks on a single dive.

Heads Up: Although there have been no documented attacks by sixgill sharks, they have impressive razor-sharp teeth and should not be harassed or disturbed in any way. Watch your gauges, as the wall is steep and it's easy to end up much deeper than anticipated.

|

Capilano I

Launched in 1892, the 130-foot Capilano I was the first Union steamship to take part in the Klondike gold rush. On Oct. 1, 1915, it struck a submerged object off Texada Island and, after makeshift repairs, continued northward. But the damage was more serious than first thought, and the crew of 16 was forced to scramble into the lifeboats and row ashore. The ship sank quickly, coming to rest upright on her keel in 130 feet of water on Grant Reefs, off the north end in the Strait of Georgia.

Dive Log: Discovered by divers in 1971, the Capilano I remains an elusive target due to its location in open water. Even when the surface visibility is poor, water clarity on the deep wreck can be excellent. The steel frame of the ship is completely covered with ghostly white plumose anemones, and schools of black rockfish hover over the hull.

Heads Up: The site is exposed to prevailing winds and is often too rough to dive safely. The wreck is so fascinating it is easy for divers to get carried away and neglect to monitor their bottom time and depth.

Sechelt Rapids

This narrow, shallow and reef-strewn passage separates the Sechelt Peninsula from mainland British Columbia. Tidal velocities here can exceed 16 knots on spring tides, creating foaming rapids, standing waves and enormous whirlpools.

Dive Log: Sessile filter and suspension feeders dominate in this current-swept passage, one of the world's fastest navigable channels. Suspended food is in constant supply, and among the most impressive of those partaking in this feast are extensive multicolored carpets of dahlia sea anemones. Sea stars, hydroids, giant barnacles and brilliant encrusting sponges paint the bottom in splashes of orange, purple, yellow and red.

Heads Up: Diving in Sechelt Rapids is rather like attempting to jaywalk across a four-lane highway--timing is everything. Dives are restricted to the brief periods of slack water, which may last for mere minutes or as much as half an hour, depending on the tidal variations on any particular day.

Row and Be Damned

At the north end of the Strait of Georgia is a tight jumble of islands that nearly creates a land bridge from Vancouver Island to the mainland. Several convoluted tidal channels wend their way through this maze of islands, the main one being Discovery Passage. Row and Be Damned is a steep rock cliff on Quadra Island that drops nearly vertically into the turbulent waters of the passage.

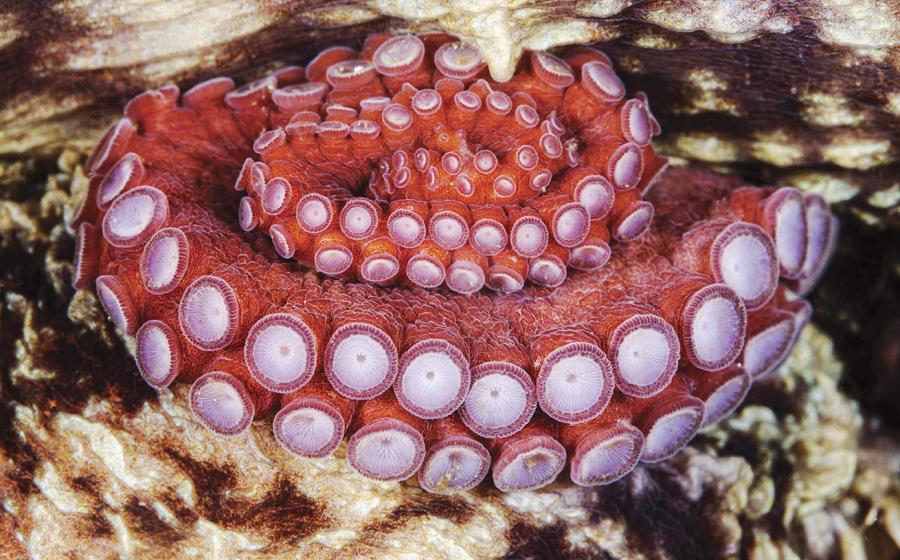

Dive Log: This is perhaps the most colorful reef in British Columbia. The bottom is a stunning carpet of sea anemones, sponges, hydroids, scallops and tubeworms, all punctuated by mats of beautiful pink strawberry anemones. Crevices are packed with red Irish lord sculpins, lingcod and tiger rockfish. Wolf eels and octopus are commonly found in the many fissures of the rocky wall.

Heads Up: Discovery Passage is a busy navigational channel and, in the summer, a popular sportfishing area. Diving is possible only at slack water, and a pickup boat is essential.

Stubbs Island

In the southeast corner of Queen Charlotte Strait near Port McNeill and Telegraph Cove are several outstanding sites, all washed by the tidal currents that sweep through Weynton Passage. This channel is one of the main junctions between the deep water of Johnstone Strait to the east and Queen Charlotte Strait farther to the west.

Dive Log: Stubbs Island is a small, rounded island that stands directly in the middle of the tidal flow. Under water, the terraced landscape forms a series of narrow ledges to a depth of about 50 feet, then plunges to depths of 200 feet. Along this side of the island stands a narrow girdle of kelp, and thousands of ghostly white plumose anemones carpet the steeper slopes. Closer to protective crevices are Puget Sound, dusky, tiger, quillback and china rockfish. Small crevices harbor decorated warbonnets, sailfin sculpins and juvenile wolf eels. Among the most conspicuous invertebrates are delicate pink and peach-colored soft corals; sometimes foot-long orange-peel nudibranchs can be seen devouring the polyps.

Heads Up: Tidal currents must be respected when diving here. Fortunately, the island creates a natural breakwater, creating a lee shore on one side of the island or the other, depending on the direction of the current.

Hunt Rock

At the north end of Vancouver Island lies Queen Charlotte Strait, a broad channel that includes some of the richest dive sites in B.C.--Browning Passage, Deserters Pass and Staples Pass. My favorite is Hunt Rock, a submerged pinnacle that lies off the east shore of Nigei Island.

Dive Log: Approaching Hunt Rock by boat, nothing is visible on the surface save for the bobbing "heads" of kelp attached to the reef 15 to 20 feet below. The reef also supports a dense thicket of incredibly wiry tree kelp, a three- to six-foot-tall seaweed that thrives in the exposed conditions. The tough stipes of these plants are home for various creatures, especially clusters of pink, orange and lavender brooding anemones.

The reef also provides shelter and food for a variety of fishes and a mated pair of wolf eels that inhabit a cave at the 60-foot level. Appropriately named Hunter and Huntress, these remarkable animals actively seek the company of divers.

Heads Up: Tidal currents, surge and fog may be encountered. This is a remote submerged pinnacle requiring a knowledgeable dive guide.

Nakwakto Rapids

Located 200 miles northwest of Vancouver on British Columbia's mainland coast, Nakwakto Rapids is one of the world's most remarkable dive sites, featuring an extraordinary oceanographic phenomenon and a biological enigma.

Dive Log: Nakwakto Rapids is a narrow channel where tidal currents peak at a blistering 16 knots. Standing defiantly in the middle of Nakwakto Rapids is a round knob of an island, a rocky pinnacle marked on the charts as Turret Rock, but better known as Tremble Island by locals. The current-raked bottom is absolutely covered with anemones and sponges. But on the most exposed ridges, where the tidal currents roar past at their fiercest, cling mounds of goose barnacles by the hundreds.

These robust relatives of the seashore barnacles use a supple stalk to glue themselves to the substrate in pillow-sized clumps below 80 feet. The discovery of this colony threw a knuckleball at marine biologists, who previously believed they were restricted to the intertidal zone.

Heads Up: The tidal currents here are nothing short of awesome, so divers must hit slack water with the precise timing of a commando raid. A vigilant dive guide in a speedy pickup boat is essential for safety.

B.C. Dive Savvy

Water Temperatures: Summer surface temps can hit 60F, but temperatures in the 40Fs persist at depths below 30 feet. Winter temps average in the mid-40Fs. A neoprene or shell-style dry suit is recommended.

Visibility: Water clarity is best in autumn and winter when visibility can reach 40 feet with local highs of 80.

For More Info: In print: 141 Dives in the Protected Waters of Washington and British Columbia, by Betty Pratt-Johnson (ISBN 091607613X). On the web: www.divebritishcolumbia.com.

B.C. Wreck Dives

Thanks to the nonprofit Artificial Reef Society of British Columbia (ARSBC), B.C. boasts some of the best wreck diving in North America. Since the late 1980s, the society has been making retired warships diver-safe and sinking them to enhance the marine environment.

The ARSBC's current project, the retired Canadian maintenance ship, HMCS Cape Breton, will become one of the largest artificial reefs in North America once it is placed off Nanaimo, B.C., in September 2001. The society's previous projects include the freighter GB Church (Aug. '91), off Portland Island; and four 366-foot destroyer escorts--the HMCS Chaudiere (Dec. '92), off Kunechin Point; the HMCS MacKenzie (Sept. '95), off Gooch Island, near Sidney; the HMCS Columbia (June '96), off Maud Island near Campbell River; and the HMCS Saskatchewan (June '97), off Snake Island near Nanaimo.

The ARSBC also helped the San Diego Oceans Foundation secure and sink the HMCS Yukon as the newest dive in San Diego's Wreck Alley, and both groups are currently lobbying the U.S. Congress for greater access to surplus U.S. warships.

July 2001

Text and Photography by Neil McDaniel

With 17,000 miles of Pacific coastline, rich waters teeming with life and dive attractions as diverse as glacier-chiseled fjords and modern steel warships, it's little wonder that British Columbia earned the 2001 RSD Readers' Choice Award for Best Overall Dive Destination in North America.

But there's a catch. B.C.'s diving conditions are far more challenging than tropical destinations. The water is cold, the visibility sometimes limited and tidal currents can really cook. But for real divers looking for real adventure, these are all part of the fun. I was asked to name just 10 of the "best" sites--a difficult task that's sure to generate plenty of arguments among my fellow British Columbians, but hey, it's my top 10. Here they are, from south to north.

Race Rocks

These rugged islets lie off the southern tip of Vancouver Island and are the most southerly point in western Canada. Marked by a distinctive black and white lighthouse, they guard the entrance to the Strait of Juan de Fuca.

Dive Log: While the coast of B.C. boasts dozens of impressive dive sites, few match this combination of diverse invertebrate life, marine mammals and rugged topside scenery. Washed daily by chilly ocean water, the rocks support shallow forests of bull kelp, which in turn shelter juvenile rockfishes and armies of grazing sea urchins. Deeper, the underwater cliffs are emblazoned with a living carpet of softball-size barnacles, pastel brooding anemones, vivid lavender hydrocorals, pink soft corals and basket stars.

More than 1,000 California and Steller's sea lions congregate on the rocks in the fall and several hundred harbor seals live at the rocks year-round.

Heads Up: The entire area inside the 20-fathom (120-foot) contour line is an ecological reserve and there is a strict ?no-touch' policy. The area is swept by tidal currents of up to six knots and is exposed to winds from all quarters. Surge can be a concern, especially on west-facing shores exposed to ocean swells that pound the rocks. Visibility varies, but the autumn months offer a reliable 40 feet or more.

Renate's Reef

The west coast of Vancouver Island is stocked with everything from rock reefs to shipwrecks. This open-water pinnacle lies in Barkley Sound and consists of two distinct ridges that rise to within 30 feet of the surface.

Dive Log: The peaks of Renate's Reef are overgrown with massive yellow clumps of calcareous staghorn bryozoan, which gives the site an uncanny resemblance to a tropical coral reef. The reef is riddled with gullies, providing home to several approachable wolf eels. Scattered throughout are clusters of plumose, fish-eating and white-spotted anemones and all manner of colorful encrusting invertebrates. The variety of rockfish is exceptional; on a single dive one can spot china, black, blue, yellowtail, tiger, copper, quillback, vermilion, canary and even yelloweye rockfish.

Heads Up: Divers need to be especially careful not to blunder into the delicate hydrocoral colonies. Surge can sometimes be a concern here and heavy ocean swells can make the reef too dangerous to dive.

Porlier Pass

This current-swept channel separates Galiano and Valdes islands, and offers several remarkable sites. As tidal currents flow through the southern Strait of Georgia, they are forced through the many narrow channels that separate the Gulf Islands. The passages, including Dodd Narrows, Gabriola Pass, Porlier Pass, Sansum Narrows and Active Pass, are among the best dive sites in the Gulf Islands because the tidal currents deliver copious amounts of food to sessile marine creatures.

Dive Log: One of the gems in Porlier Pass is Boscowitz Rock, a kelp-fringed pinnacle that lies only a stone's throw off Race Point. The reef is loaded with marine life, including carpets of dahlia, plumose and brooding anemones, basket stars, blue-clawed lithode crabs and sprawling violet patches of encrusting hydrocorals.

Near the center of the pass on Virago Rock lie the battered remains of the steam tug Point Grey. It stranded on the then unmarked reef in 1949. A decade later a violent storm toppled the wreck onto a shallow ledge, where the fast currents soon transformed the steel skeleton into a living reef. The ship provides underwater photographers with excellent wide-angle opportunities. On autumn days, visibility is good enough to see more than half of its 105-foot length.

Heads Up: Porlier Pass is a heavily transited navigational passage. Beware boat traffic.

Flora Islet

This small islet lies off the easternmost tip of Hornby Island, a scenic Gulf Island lying about halfway along the east coast of Vancouver Island in the Strait of Georgia.

Dive Log: Flora Islet features a steep, terraced drop-off that plunges dramatically into depths well over 600 feet and offers the chance to swim with sixgill sharks. Nobody knows why these deep-water behemoths regularly venture into the shallows here, but this is your chance to swim with eight- to 14-foot-long sharks as they slowly cruise the wall, oblivious to the attentions of excited divers. The parade of sixgill sharks begins in the late spring and continues into the early autumn. During the summer months it is not uncommon to see two or three different sharks on a single dive.

Heads Up: Although there have been no documented attacks by sixgill sharks, they have impressive razor-sharp teeth and should not be harassed or disturbed in any way. Watch your gauges, as the wall is steep and it's easy to end up much deeper than anticipated.

|

Capilano I

Launched in 1892, the 130-foot Capilano I was the first Union steamship to take part in the Klondike gold rush. On Oct. 1, 1915, it struck a submerged object off Texada Island and, after makeshift repairs, continued northward. But the damage was more serious than first thought, and the crew of 16 was forced to scramble into the lifeboats and row ashore. The ship sank quickly, coming to rest upright on her keel in 130 feet of water on Grant Reefs, off the north end in the Strait of Georgia.

Dive Log: Discovered by divers in 1971, the Capilano I remains an elusive target due to its location in open water. Even when the surface visibility is poor, water clarity on the deep wreck can be excellent. The steel frame of the ship is completely covered with ghostly white plumose anemones, and schools of black rockfish hover over the hull.

Heads Up: The site is exposed to prevailing winds and is often too rough to dive safely. The wreck is so fascinating it is easy for divers to get carried away and neglect to monitor their bottom time and depth.

Sechelt Rapids

This narrow, shallow and reef-strewn passage separates the Sechelt Peninsula from mainland British Columbia. Tidal velocities here can exceed 16 knots on spring tides, creating foaming rapids, standing waves and enormous whirlpools.

Dive Log: Sessile filter and suspension feeders dominate in this current-swept passage, one of the world's fastest navigable channels. Suspended food is in constant supply, and among the most impressive of those partaking in this feast are extensive multicolored carpets of dahlia sea anemones. Sea stars, hydroids, giant barnacles and brilliant encrusting sponges paint the bottom in splashes of orange, purple, yellow and red.

Heads Up: Diving in Sechelt Rapids is rather like attempting to jaywalk across a four-lane highway--timing is everything. Dives are restricted to the brief periods of slack water, which may last for mere minutes or as much as half an hour, depending on the tidal variations on any particular day.

Row and Be Damned

At the north end of the Strait of Georgia is a tight jumble of islands that nearly creates a land bridge from Vancouver Island to the mainland. Several convoluted tidal channels wend their way through this maze of islands, the main one being Discovery Passage. Row and Be Damned is a steep rock cliff on Quadra Island that drops nearly vertically into the turbulent waters of the passage.

Dive Log: This is perhaps the most colorful reef in British Columbia. The bottom is a stunning carpet of sea anemones, sponges, hydroids, scallops and tubeworms, all punctuated by mats of beautiful pink strawberry anemones. Crevices are packed with red Irish lord sculpins, lingcod and tiger rockfish. Wolf eels and octopus are commonly found in the many fissures of the rocky wall.

Heads Up: Discovery Passage is a busy navigational channel and, in the summer, a popular sportfishing area. Diving is possible only at slack water, and a pickup boat is essential.

Stubbs Island

In the southeast corner of Queen Charlotte Strait near Port McNeill and Telegraph Cove are several outstanding sites, all washed by the tidal currents that sweep through Weynton Passage. This channel is one of the main junctions between the deep water of Johnstone Strait to the east and Queen Charlotte Strait farther to the west.

Dive Log: Stubbs Island is a small, rounded island that stands directly in the middle of the tidal flow. Under water, the terraced landscape forms a series of narrow ledges to a depth of about 50 feet, then plunges to depths of 200 feet. Along this side of the island stands a narrow girdle of kelp, and thousands of ghostly white plumose anemones carpet the steeper slopes. Closer to protective crevices are Puget Sound, dusky, tiger, quillback and china rockfish. Small crevices harbor decorated warbonnets, sailfin sculpins and juvenile wolf eels. Among the most conspicuous invertebrates are delicate pink and peach-colored soft corals; sometimes foot-long orange-peel nudibranchs can be seen devouring the polyps.

Heads Up: Tidal currents must be respected when diving here. Fortunately, the island creates a natural breakwater, creating a lee shore on one side of the island or the other, depending on the direction of the current.

Hunt Rock

At the north end of Vancouver Island lies Queen Charlotte Strait, a broad channel that includes some of the richest dive sites in B.C.--Browning Passage, Deserters Pass and Staples Pass. My favorite is Hunt Rock, a submerged pinnacle that lies off the east shore of Nigei Island.

Dive Log: Approaching Hunt Rock by boat, nothing is visible on the surface save for the bobbing "heads" of kelp attached to the reef 15 to 20 feet below. The reef also supports a dense thicket of incredibly wiry tree kelp, a three- to six-foot-tall seaweed that thrives in the exposed conditions. The tough stipes of these plants are home for various creatures, especially clusters of pink, orange and lavender brooding anemones.

The reef also provides shelter and food for a variety of fishes and a mated pair of wolf eels that inhabit a cave at the 60-foot level. Appropriately named Hunter and Huntress, these remarkable animals actively seek the company of divers.

Heads Up: Tidal currents, surge and fog may be encountered. This is a remote submerged pinnacle requiring a knowledgeable dive guide.

Nakwakto Rapids

Located 200 miles northwest of Vancouver on British Columbia's mainland coast, Nakwakto Rapids is one of the world's most remarkable dive sites, featuring an extraordinary oceanographic phenomenon and a biological enigma.

Dive Log: Nakwakto Rapids is a narrow channel where tidal currents peak at a blistering 16 knots. Standing defiantly in the middle of Nakwakto Rapids is a round knob of an island, a rocky pinnacle marked on the charts as Turret Rock, but better known as Tremble Island by locals. The current-raked bottom is absolutely covered with anemones and sponges. But on the most exposed ridges, where the tidal currents roar past at their fiercest, cling mounds of goose barnacles by the hundreds.

These robust relatives of the seashore barnacles use a supple stalk to glue themselves to the substrate in pillow-sized clumps below 80 feet. The discovery of this colony threw a knuckleball at marine biologists, who previously believed they were restricted to the intertidal zone.

Heads Up: The tidal currents here are nothing short of awesome, so divers must hit slack water with the precise timing of a commando raid. A vigilant dive guide in a speedy pickup boat is essential for safety.

B.C. Dive Savvy

Water Temperatures: Summer surface temps can hit 60F, but temperatures in the 40Fs persist at depths below 30 feet. Winter temps average in the mid-40Fs. A neoprene or shell-style dry suit is recommended.

Visibility: Water clarity is best in autumn and winter when visibility can reach 40 feet with local highs of 80.

For More Info: In print: 141 Dives in the Protected Waters of Washington and British Columbia, by Betty Pratt-Johnson (ISBN 091607613X). On the web: www.divebritishcolumbia.com.

B.C. Wreck Dives

Thanks to the nonprofit Artificial Reef Society of British Columbia (ARSBC), B.C. boasts some of the best wreck diving in North America. Since the late 1980s, the society has been making retired warships diver-safe and sinking them to enhance the marine environment.

The ARSBC's current project, the retired Canadian maintenance ship, HMCS Cape Breton, will become one of the largest artificial reefs in North America once it is placed off Nanaimo, B.C., in September 2001. The society's previous projects include the freighter GB Church (Aug. '91), off Portland Island; and four 366-foot destroyer escorts--the HMCS Chaudiere (Dec. '92), off Kunechin Point; the HMCS MacKenzie (Sept. '95), off Gooch Island, near Sidney; the HMCS Columbia (June '96), off Maud Island near Campbell River; and the HMCS Saskatchewan (June '97), off Snake Island near Nanaimo.

The ARSBC also helped the San Diego Oceans Foundation secure and sink the HMCS Yukon as the newest dive in San Diego's Wreck Alley, and both groups are currently lobbying the U.S. Congress for greater access to surplus U.S. warships.