Where to Scuba Dive with Killer Whales

Orcas — aka killer whales — are one of the most recognizable species of marine mammals in the world, thanks to their unfortunate history in captivity at theme parks like SeaWorld. But to understand the sheer power and intelligence of these creatures, there’s no substitute for seeing them in the wild.

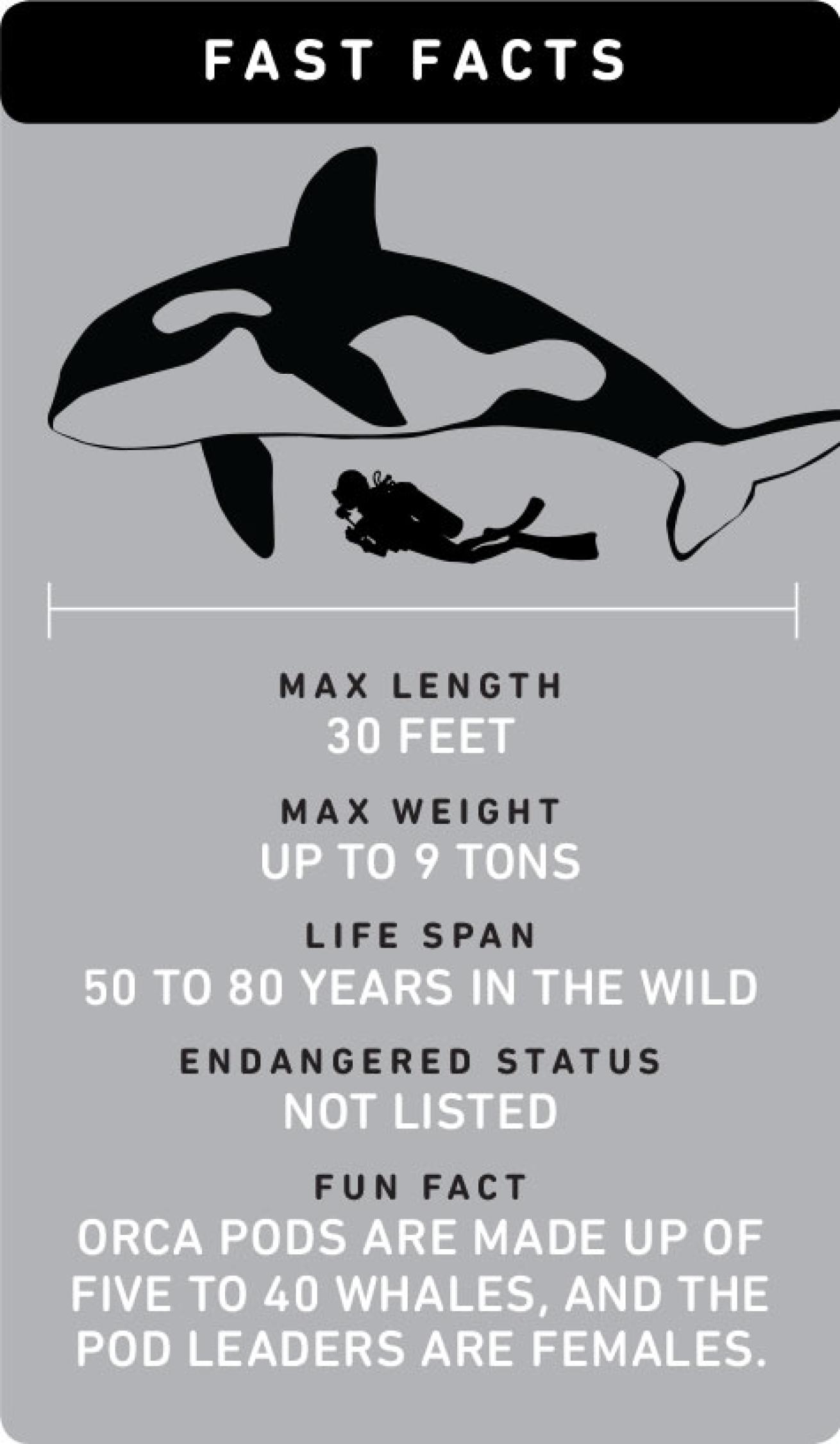

Despite the name killer whale, orcas are actually the largest members of the dolphin family, growing up to 30 feet long and weighing nearly 9 tons. In fact, some believe their name is a misreading of the moniker "whale killers,” given by Spanish sailors, which better describes their habit of hunting and killing large whales, though whales aren’t the only prey on the menu for orcas.

What they eat depends on which type of orca is doing the hunting. There are three distinct subgroups: residents, transients and open-ocean pods. Resident orcas stay in one area, eating mostly fish; transients migrate over a coastal range, hunting marine mammals such as seals, dolphins and whales. A third population of offshore orcas lives exclusively in the open Pacific Ocean, where they’ve been hard to study, though evidence shows sharks might be part of their diet.

Orcas are found all over the world, from the salmon-rich waters of North America’s Pacific Northwest to the shores of Patagonia, where they chase seals right onto the beaches, sliding across the sand to snatch their prey before wriggling back into the water.

Divers looking to go face to face with orcas in the water should head to northern Norway from November to January, when hundreds of killer whales descend on a vast herring migration. Sven Gust, owner of arctic dive operation Northern Explorers, has led tours to snorkel with orcas in this herring run for more than 15 years.

“We did our first tours in the Tysfjord area, but the herring change their route every 10 to 20 years to get rid of the predators,” Gust says. “Now we see them in the area between Andenes and Tromsø, and we’re also seeing other whales — humpbacks, finbacks, sei whales, pilot whales and minke whales.”

Gust says around 1,000 orcas visit the area every winter; he uses two different techniques to get divers in the water with them. “Most commonly, we use fast RIBs to drop the divers in front of the whales, but you only get a short look and a minimum of interaction,” he says. “The best situation is to find where the feeding whales push the herring into shallow water. Here you get the best action, but it’s also a bit scary.”

That’s because the orcas blast through the school, trying to smack the herring with their tail fins, which gets the school panicked and moving fast. “You might have clear viz one second, and in the next you’re inside a black wall of herring,” Gust says. “I am not scared about the orcas — they’re very in control — but I wouldn’t trust humpbacks when they try to eat a whole shoal of fish at once.”

Mark CarwardineYou've seen orcas at theme parks — but imagine what it's like to see them in the wild.

Orcas — aka killer whales — are one of the most recognizable species of marine mammals in the world, thanks to their unfortunate history in captivity at theme parks like SeaWorld. But to understand the sheer power and intelligence of these creatures, there’s no substitute for seeing them in the wild.

ShutterstockFrom November to January, divers can go face-to-face with orcas in Norway.

Despite the name killer whale, orcas are actually the largest members of the dolphin family, growing up to 30 feet long and weighing nearly 9 tons. In fact, some believe their name is a misreading of the moniker "whale killers,” given by Spanish sailors, which better describes their habit of hunting and killing large whales, though whales aren’t the only prey on the menu for orcas.

ShutterstockThere are three distinct subgroups of orca whales: residents, transients and open-ocean pods.

What they eat depends on which type of orca is doing the hunting. There are three distinct subgroups: residents, transients and open-ocean pods. Resident orcas stay in one area, eating mostly fish; transients migrate over a coastal range, hunting marine mammals such as seals, dolphins and whales. A third population of offshore orcas lives exclusively in the open Pacific Ocean, where they’ve been hard to study, though evidence shows sharks might be part of their diet.

ShutterstockOrca whales are actually not whales at all — they belong to the dolphin family.

Orcas are found all over the world, from the salmon-rich waters of North America’s Pacific Northwest to the shores of Patagonia, where they chase seals right onto the beaches, sliding across the sand to snatch their prey before wriggling back into the water.

ShutterstockOrcas can grow to a max length of 30 feet and weigh up to 9 tons.

Divers looking to go face to face with orcas in the water should head to northern Norway from November to January, when hundreds of killer whales descend on a vast herring migration. Sven Gust, owner of arctic dive operation Northern Explorers, has led tours to snorkel with orcas in this herring run for more than 15 years.

“We did our first tours in the Tysfjord area, but the herring change their route every 10 to 20 years to get rid of the predators,” Gust says. “Now we see them in the area between Andenes and Tromsø, and we’re also seeing other whales — humpbacks, finbacks, sei whales, pilot whales and minke whales.”

Gust says around 1,000 orcas visit the area every winter; he uses two different techniques to get divers in the water with them. “Most commonly, we use fast RIBs to drop the divers in front of the whales, but you only get a short look and a minimum of interaction,” he says. “The best situation is to find where the feeding whales push the herring into shallow water. Here you get the best action, but it’s also a bit scary.”

That’s because the orcas blast through the school, trying to smack the herring with their tail fins, which gets the school panicked and moving fast. “You might have clear viz one second, and in the next you’re inside a black wall of herring,” Gust says. “I am not scared about the orcas — they’re very in control — but I wouldn’t trust humpbacks when they try to eat a whole shoal of fish at once.”