The Dark Side

The Zodiac skips over the mirror-calm waters of the fjord, leaving behind a foaming V-shaped wake. Time is of the essence. Tide waits for no diver, and the slack-water window is a mere 15 minutes. We don’t want to miss this morning dive.

The Zodiac slows to a crawl, and Tommy and I start to kit up. Tommy has seen the reef many times, but this is only my second visit. Although we know what to expect, there’s a sense of urgency and excitement. Tommy dons his twin set topped with helium, and I throw on a pair of 120s pumped with EAN26 and a stage bottle with EAN50.

Slipping over the side of the Zodiac and into the water is a blessed relief, easing the impossible strain of trying to remain comfortable with half a dive shop’s stock on my back. Slack water won’t last, and if we want to dive, we have to go now. With a final OK we descend, the rope sliding through my glove as we drop into the inky-black water.

The only known example of a cold-water coral reef within scuba range, Skarnsundet sits at 140 feet in Norway’s Trondheim fjord. Built by hard, stony corals that normally live in the dark depths ranging from 500 to 3,000 feet, it’s an evolutionary marvel that can be dived only twice a day, when the currents peter out before the tide changes.

Found in the depths from the Arctic to the tropics, cold-water stony-coral-reef systems live in complete darkness and tolerate bone-chilling temperatures. These reefs are unlike their tropical cousins, which demand both warmth and sunlight to thrive. Until the advent of deepwater oil exploration, the extent of these cold-water reefs were unknown; but from surveys along the Norwegian coast and North Atlantic, we now realize just how extensive they are, anchored along the edge of the continental shelf or the slopes of seamounts.

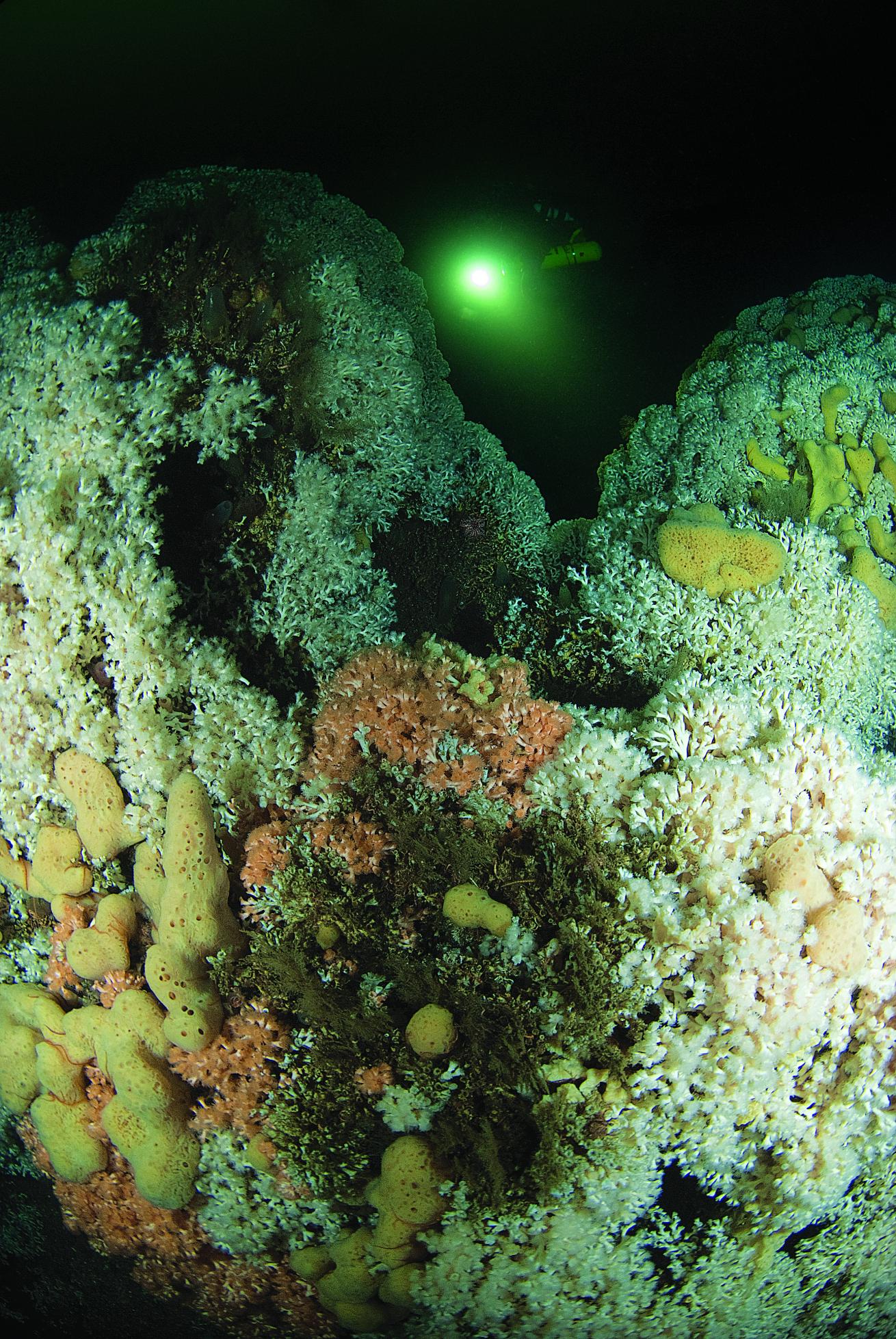

Ghostly pale white orbs appear from the black. Thinking my eyes have fooled me, I check my dive computer. I’ve just dropped past the 90-foot mark and still have another 50 feet before I hit the bottom. Already though I can see the entire reef laid out before me. Almost pure-white mounds of hard coral punch out of the silt, and from this depth I realize just how small the reef is — the coral heads would fit into an Olympic-size swimming pool, with room to spare.

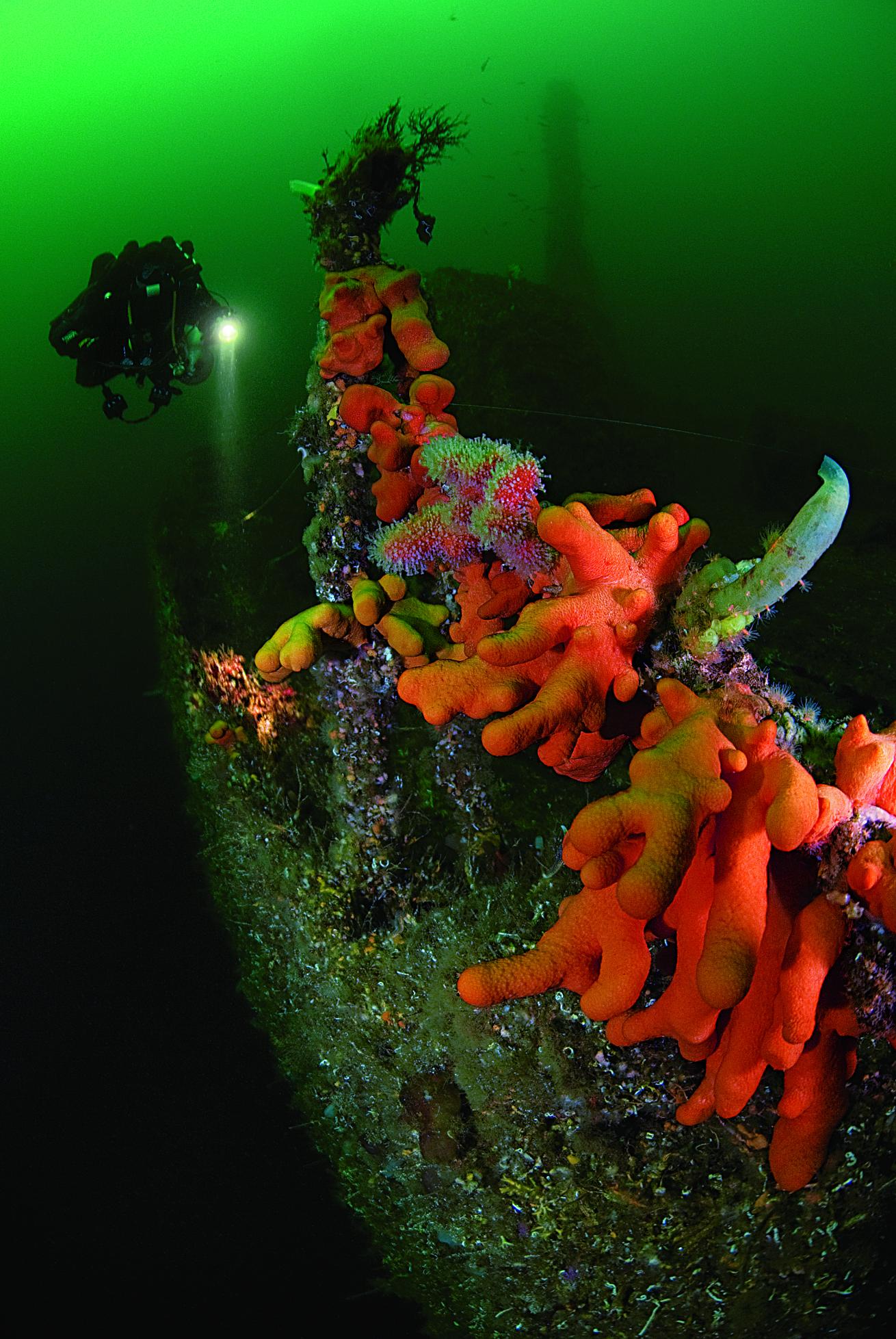

Adjusting my buoyancy, I slow the descent. Narcosis at 140 feet slows my thinking, but I can’t help marvel at the bright-orange gorgonians, swaying gently in the slight current, caught in Tommy’s light. Slowly, my eyes adjust to the gloom while my brain engages with the camera, whipping off the port cover, powering up the strobes and starting to think about capturing the scene. Before me, the view looks familiar yet feels so wrong. Hard corals, with their delicate polyps open and feeding, remind me of sunlit dives in the tropics, but the bone-chill of the water is stinging my exposed skin. Only the drysuit keeps the cold at bay. This place is just plain weird — I feel like I’ve crash-landed on an alien planet.

It normally takes a submersible to get an up-close view of a deep lophelia reef. The reef in Trondheim has decided to grow in the (relative) shallows on a narrow ridge at a mere 140 feet, surrounded on both sides by water that plunges to 650 feet. Twice a day, the tide surges over the ridge, bringing nutrition. Unlike their tropical cousins that rely on the symbiotic relationship with algae for their food, lophelia corals feed on “marine snow” — the little bits and pieces of detritus that filters down from the sunlit waters high above.

The extents of lophelia reefs are still being explored, but recent changes in fishing practices are damaging these fragile habitats. As traditional catches like cod declined, fishing fleets targeted deepwater fish and, just like the tropics where there is shelter and food, there are fish. Lophelia reefs are as fragile as any coral, and heavy-towed trawl nets can reduce a pristine reef to rubble in a single pass. Norway and the United Kingdom have declared seabed areas around deepwater coral reefs as protected areas and towed trawl fishing gear is banned, protecting the fragile reefs from further damage.

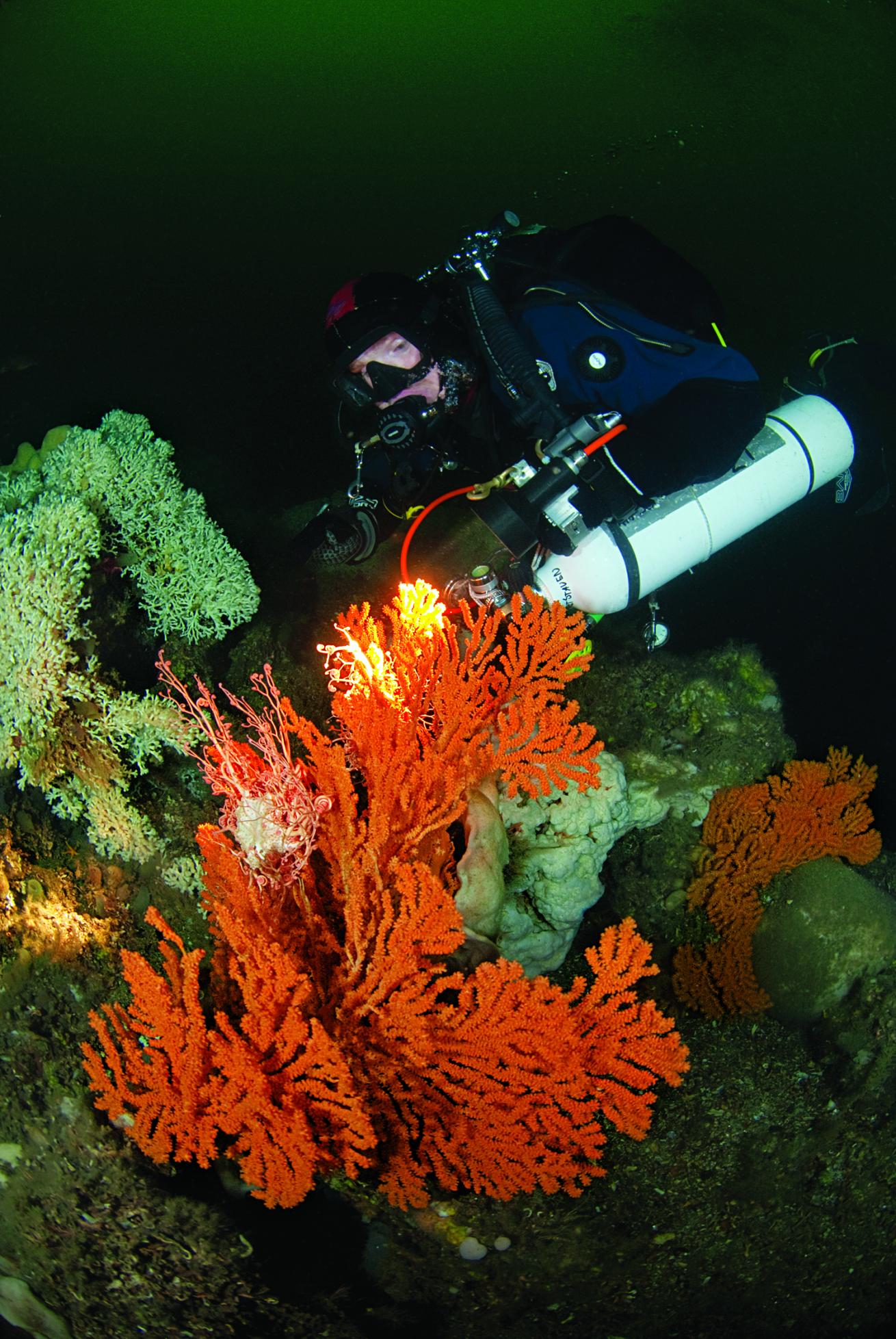

It would be easy to fin around the entire reef in less than five minutes, but I want to savor the experience and take my time. Just 14 minutes into the dive I find the solitary example of a “sea tree,” something I saw on my first visit but wanted to photograph again. Deep red and with branching arms, the polyps of Paragorgia arborea were open and feeding, an event some had waited years to witness. Tangled within the branches sat a basket starfish, its multitude of arms embracing its host.

Out of the corner of my mask I see Tommy’s torch, flicking from side to side from the foot of the line. Our 22 minutes of bottom time are up, and in the shelter of the reef I’m oblivious to the rising current. It’s time to leave before we’re swept from the ridge. I fin across the seabed to the rope, giving the quick thumbs up as we head toward the surface. At 60 feet we switch to the stage cylinders, letting the higher oxygen content cut the mandatory decompression stops from 27 minutes to 17. I point downward and give Tommy a big OK sign, a view confirmed by his eyes shining and cheeks bulging under the mask — in a way only divers who are smiling with a regulator in the mouth can do. Deco stops completed, we dekit alongside the Zodiac. “How was it?” the captain asks. My big grin says it all — cold, dark, deep and exposed to tides, but like no other dive spot on the planet.

As good as the Skarnsundet reef is, for the wreck diver, a reef dive — no matter how special — is a waste of good gas. Luckily, Trondheim fjord and the surrounds have well-preserved rust aplenty. In fact, two German World War II vintage Heinkel HE115 seaplanes lie just 300 feet from the Trondheim dock; the planes sank at their moorings during a bombing raid and gently settled into the silt.

Tucked in the shadows of the surrounding mountains, the site is sheltered but pitch dark at 145 feet. To explore these wrecks would take some serious firepower; my buddy Robert is a help in this regard. A rebreather-equipped cave diver, he likes to build his own dive lights. Good thing too, for as we drop to the first wreck his two 250-watt lamps light up the “night,” revealing the still-shiny aluminum wing of the first plane. The leading edge of the wing guides us toward the starboard BMW engine, and beyond to the cockpit and fuselage. We follow the rope across the silt to the second Heinkel, around 350 feet away from the first. It might seem strange to fin 350 feet to see the same type of aircraft, but both wrecks are tiny when compared with a ship, and diver crowding would have quickly ended the photo shoot.

To see both wrecks demands precise gas management, and I pause several times to check contents and gauges as Robert and I fin across the gap. Over the years, the second Heinkel has slowly settled even farther into the silt, but the cockpit retains some of the original flight controls. As Robert lights up the wreck, I set to work photographing the starboard engine, conscious that one careless fin kick will shroud the wreck in light, fluffy silt.

Two days later, we visit the wreck of a large WWII freighter, the Consul Carl Fisser. Sunk on the May 3, 1942, by RAF, this 5,900-ton wreck now sits perfectly upright on a slope, with the stern at 65 feet and the bow in 150 feet. At the stern, the deep green of fjord water and natural light offset the orange hues of dead-man’s finger sponges. This kind of landscape sets the photographer’s juices in me flowing, and I subconsciously start planning my attack for a second dive.

Robert and I fin slowly along the starboard rail, past the aft holds and deck winches, and toward the bridge. In 60 feet of clear water, the sheer size of this wreck dominates the view beyond the mask. With his impeccable buoyancy control, Robert fins down the starboard companionway, past the fire-damaged bridge, before exiting above the steps down to the main deck. There, our eyes adjust to the gloom, and we start to see the winches, jibs and anchor chains on the forward decks.

Finning over the bow at 150 feet, I turn and look back to see a ghostly ship looming out of the wall of dark green fog; but I’m already in deco and can’t linger. We turn and follow the port rail back to the ascent line. When wrecks are well preserved, navigation is easy and we pause at the engine skylights. It’s possible to penetrate the wreck here, but the engine room bottoms out at 180 feet and is very silty — not the place to venture without training and planning, and a whole lot more gas. Back at the stern, I’m in sport-diving depths, but the mandatory stops are approaching 30 minutes, and there’s just time to check out the emergency steering gear before switching to 50 percent deco gas and starting the ascent.

At the first deco stop, I can still see the stern rail with its row of orange sponges. My thoughts start to wander, and in my mind’s eye an image forms, but it needs a bit of help from the rest of the divers. I really want a second dive on the Fisser, just to get that shot. I just hope the rest of the divers are equally keen.

Deco over and back on the dive boat, I start to dekit and hear a snippet of conversation that quickly warms me after the bone-chilling cold. “Too big for one dive,” says one of the other divers. The team is already planning a second dive. “I have an idea and need your help,” I say. And the photo shoot for dive two begins.

What It Takes

At 140-plus feet deep, the reef at Skarnsundet and the wrecks in Trondheim are advanced dives beyond the range of recreational scuba; technical dive training and skills are prerequisite. With water temperatures hovering around 52 degrees F, drysuit skills are a must and advanced nitrox certification is highly beneficial, but bottom time will be limited to single digits without decompression skills. A 50 percent to 80 percent nitrox mix in the stage cylinder for accelerated decompression limits exposure to the cold and ensures divers exit the water before the tide on the reef really starts to run. Dykkersport Trondheim requires deep-diving experience (140-plus feet), excellent buoyancy control and drysuit diving for Skarnsundet. All these qualifications are subject to one to two checkout dives before a dive on the reef. Marker-buoy deployment and midwater decompression stops are required for some of the wreck dives.

Need to Know

Getting There Fly to Trondheim (TRD) on SAS from European hubs like London, Copenhagen and Amsterdam, or Norway’s capital, Oslo. Taxis are prohibitively expensive (as are most things in Trondheim). The most cost-effective way of getting from the airport to the city is using the Flybussen service, with an hourly service to the central bus station.

When to Go Winter is cold, with average daytime highs of 32 degrees F. Spring and summer can experience plankton blooms, but autumn gives the best chance of fine weather and good underwater visibility.

Dive Conditions Underwater visibility can range from 30 feet to 90 feet in September and October. Generally speaking, deeper dives tend to be darker, but clearer water lies beneath the plankton bloom. Water temperature in autumn (the warmest season) ranges from 48 degrees F at depth to 52 degrees F in the shallows.

Operators Dykkersport Trondheim A/S is close to the city center and has close links with the only live-aboard in the region, the M/S Sula ( www.liveaboard.no ) — a large, robust and comfortable dive boat that regularly makes local expeditions to explore the wrecks and reefs of Trondheim fjord.

Price Tag Norway can be a criminally expensive place to eat and drink, so a live-aboard is a good option (and Sula has the cheapest beer in town): One week aboard the Sula is $2,680 and includes food, accommodations and air fills. One dive with the Zodiac is $90, two dives is $144.

The Zodiac skips over the mirror-calm waters of the fjord, leaving behind a foaming V-shaped wake. Time is of the essence. Tide waits for no diver, and the slack-water window is a mere 15 minutes. We don’t want to miss this morning dive.

The Zodiac slows to a crawl, and Tommy and I start to kit up. Tommy has seen the reef many times, but this is only my second visit. Although we know what to expect, there’s a sense of urgency and excitement. Tommy dons his twin set topped with helium, and I throw on a pair of 120s pumped with EAN26 and a stage bottle with EAN50.

Slipping over the side of the Zodiac and into the water is a blessed relief, easing the impossible strain of trying to remain comfortable with half a dive shop’s stock on my back. Slack water won’t last, and if we want to dive, we have to go now. With a final OK we descend, the rope sliding through my glove as we drop into the inky-black water.

The only known example of a cold-water coral reef within scuba range, Skarnsundet sits at 140 feet in Norway’s Trondheim fjord. Built by hard, stony corals that normally live in the dark depths ranging from 500 to 3,000 feet, it’s an evolutionary marvel that can be dived only twice a day, when the currents peter out before the tide changes.

Found in the depths from the Arctic to the tropics, cold-water stony-coral-reef systems live in complete darkness and tolerate bone-chilling temperatures. These reefs are unlike their tropical cousins, which demand both warmth and sunlight to thrive. Until the advent of deepwater oil exploration, the extent of these cold-water reefs were unknown; but from surveys along the Norwegian coast and North Atlantic, we now realize just how extensive they are, anchored along the edge of the continental shelf or the slopes of seamounts.

Ghostly pale white orbs appear from the black. Thinking my eyes have fooled me, I check my dive computer. I’ve just dropped past the 90-foot mark and still have another 50 feet before I hit the bottom. Already though I can see the entire reef laid out before me. Almost pure-white mounds of hard coral punch out of the silt, and from this depth I realize just how small the reef is — the coral heads would fit into an Olympic-size swimming pool, with room to spare.

Adjusting my buoyancy, I slow the descent. Narcosis at 140 feet slows my thinking, but I can’t help marvel at the bright-orange gorgonians, swaying gently in the slight current, caught in Tommy’s light. Slowly, my eyes adjust to the gloom while my brain engages with the camera, whipping off the port cover, powering up the strobes and starting to think about capturing the scene. Before me, the view looks familiar yet feels so wrong. Hard corals, with their delicate polyps open and feeding, remind me of sunlit dives in the tropics, but the bone-chill of the water is stinging my exposed skin. Only the drysuit keeps the cold at bay. This place is just plain weird — I feel like I’ve crash-landed on an alien planet.

It normally takes a submersible to get an up-close view of a deep lophelia reef. The reef in Trondheim has decided to grow in the (relative) shallows on a narrow ridge at a mere 140 feet, surrounded on both sides by water that plunges to 650 feet. Twice a day, the tide surges over the ridge, bringing nutrition. Unlike their tropical cousins that rely on the symbiotic relationship with algae for their food, lophelia corals feed on “marine snow” — the little bits and pieces of detritus that filters down from the sunlit waters high above.

The extents of lophelia reefs are still being explored, but recent changes in fishing practices are damaging these fragile habitats. As traditional catches like cod declined, fishing fleets targeted deepwater fish and, just like the tropics where there is shelter and food, there are fish. Lophelia reefs are as fragile as any coral, and heavy-towed trawl nets can reduce a pristine reef to rubble in a single pass. Norway and the United Kingdom have declared seabed areas around deepwater coral reefs as protected areas and towed trawl fishing gear is banned, protecting the fragile reefs from further damage.

It would be easy to fin around the entire reef in less than five minutes, but I want to savor the experience and take my time. Just 14 minutes into the dive I find the solitary example of a “sea tree,” something I saw on my first visit but wanted to photograph again. Deep red and with branching arms, the polyps of Paragorgia arborea were open and feeding, an event some had waited years to witness. Tangled within the branches sat a basket starfish, its multitude of arms embracing its host.

Out of the corner of my mask I see Tommy’s torch, flicking from side to side from the foot of the line. Our 22 minutes of bottom time are up, and in the shelter of the reef I’m oblivious to the rising current. It’s time to leave before we’re swept from the ridge. I fin across the seabed to the rope, giving the quick thumbs up as we head toward the surface. At 60 feet we switch to the stage cylinders, letting the higher oxygen content cut the mandatory decompression stops from 27 minutes to 17. I point downward and give Tommy a big OK sign, a view confirmed by his eyes shining and cheeks bulging under the mask — in a way only divers who are smiling with a regulator in the mouth can do. Deco stops completed, we dekit alongside the Zodiac. “How was it?” the captain asks. My big grin says it all — cold, dark, deep and exposed to tides, but like no other dive spot on the planet.

As good as the Skarnsundet reef is, for the wreck diver, a reef dive — no matter how special — is a waste of good gas. Luckily, Trondheim fjord and the surrounds have well-preserved rust aplenty. In fact, two German World War II vintage Heinkel HE115 seaplanes lie just 300 feet from the Trondheim dock; the planes sank at their moorings during a bombing raid and gently settled into the silt.

Tucked in the shadows of the surrounding mountains, the site is sheltered but pitch dark at 145 feet. To explore these wrecks would take some serious firepower; my buddy Robert is a help in this regard. A rebreather-equipped cave diver, he likes to build his own dive lights. Good thing too, for as we drop to the first wreck his two 250-watt lamps light up the “night,” revealing the still-shiny aluminum wing of the first plane. The leading edge of the wing guides us toward the starboard BMW engine, and beyond to the cockpit and fuselage. We follow the rope across the silt to the second Heinkel, around 350 feet away from the first. It might seem strange to fin 350 feet to see the same type of aircraft, but both wrecks are tiny when compared with a ship, and diver crowding would have quickly ended the photo shoot.

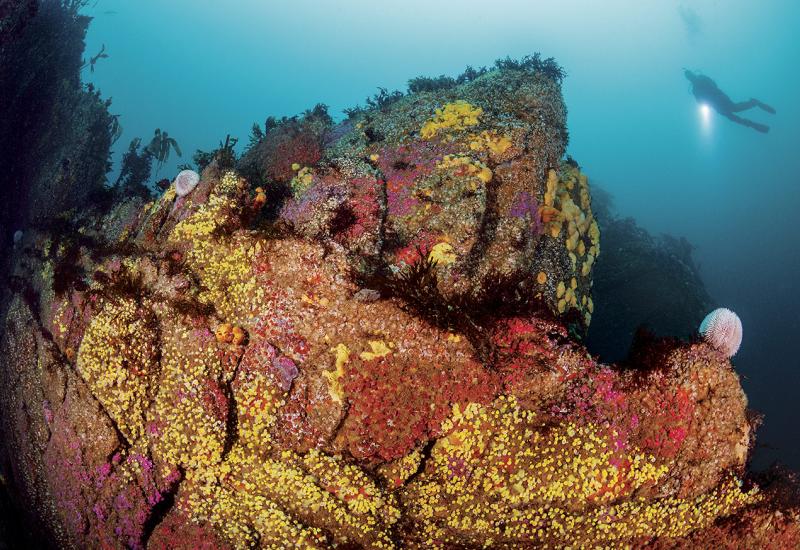

Simon BrownA diver lights a section of the Consul Car Fisser covered in dead man's finger coral in Trondheim, Norway.

To see both wrecks demands precise gas management, and I pause several times to check contents and gauges as Robert and I fin across the gap. Over the years, the second Heinkel has slowly settled even farther into the silt, but the cockpit retains some of the original flight controls. As Robert lights up the wreck, I set to work photographing the starboard engine, conscious that one careless fin kick will shroud the wreck in light, fluffy silt.

Two days later, we visit the wreck of a large WWII freighter, the Consul Carl Fisser. Sunk on the May 3, 1942, by RAF, this 5,900-ton wreck now sits perfectly upright on a slope, with the stern at 65 feet and the bow in 150 feet. At the stern, the deep green of fjord water and natural light offset the orange hues of dead-man’s finger sponges. This kind of landscape sets the photographer’s juices in me flowing, and I subconsciously start planning my attack for a second dive.

Simon BrownWhite and peach variants of lophelia cold-water corals, typically found from 500 to 3,000 feet thrive on a reef in just 140 feet.

Robert and I fin slowly along the starboard rail, past the aft holds and deck winches, and toward the bridge. In 60 feet of clear water, the sheer size of this wreck dominates the view beyond the mask. With his impeccable buoyancy control, Robert fins down the starboard companionway, past the fire-damaged bridge, before exiting above the steps down to the main deck. There, our eyes adjust to the gloom, and we start to see the winches, jibs and anchor chains on the forward decks.

Finning over the bow at 150 feet, I turn and look back to see a ghostly ship looming out of the wall of dark green fog; but I’m already in deco and can’t linger. We turn and follow the port rail back to the ascent line. When wrecks are well preserved, navigation is easy and we pause at the engine skylights. It’s possible to penetrate the wreck here, but the engine room bottoms out at 180 feet and is very silty — not the place to venture without training and planning, and a whole lot more gas. Back at the stern, I’m in sport-diving depths, but the mandatory stops are approaching 30 minutes, and there’s just time to check out the emergency steering gear before switching to 50 percent deco gas and starting the ascent.

Simon BrownGorgonians brighten the Skarnsundet reef.

At the first deco stop, I can still see the stern rail with its row of orange sponges. My thoughts start to wander, and in my mind’s eye an image forms, but it needs a bit of help from the rest of the divers. I really want a second dive on the Fisser, just to get that shot. I just hope the rest of the divers are equally keen.

Deco over and back on the dive boat, I start to dekit and hear a snippet of conversation that quickly warms me after the bone-chilling cold. “Too big for one dive,” says one of the other divers. The team is already planning a second dive. “I have an idea and need your help,” I say. And the photo shoot for dive two begins.

Simon BrownA BMW radial engine on the Heinkel HE115 wreck.

What It Takes

At 140-plus feet deep, the reef at Skarnsundet and the wrecks in Trondheim are advanced dives beyond the range of recreational scuba; technical dive training and skills are prerequisite. With water temperatures hovering around 52 degrees F, drysuit skills are a must and advanced nitrox certification is highly beneficial, but bottom time will be limited to single digits without decompression skills. A 50 percent to 80 percent nitrox mix in the stage cylinder for accelerated decompression limits exposure to the cold and ensures divers exit the water before the tide on the reef really starts to run. Dykkersport Trondheim requires deep-diving experience (140-plus feet), excellent buoyancy control and drysuit diving for Skarnsundet. All these qualifications are subject to one to two checkout dives before a dive on the reef. Marker-buoy deployment and midwater decompression stops are required for some of the wreck dives.

Simon BrownA diver explores the winch and deck crane on the Consul Car Fisser.

Need to Know

Getting There Fly to Trondheim (TRD) on SAS from European hubs like London, Copenhagen and Amsterdam, or Norway’s capital, Oslo. Taxis are prohibitively expensive (as are most things in Trondheim). The most cost-effective way of getting from the airport to the city is using the Flybussen service, with an hourly service to the central bus station.

When to Go Winter is cold, with average daytime highs of 32 degrees F. Spring and summer can experience plankton blooms, but autumn gives the best chance of fine weather and good underwater visibility.

Dive Conditions Underwater visibility can range from 30 feet to 90 feet in September and October. Generally speaking, deeper dives tend to be darker, but clearer water lies beneath the plankton bloom. Water temperature in autumn (the warmest season) ranges from 48 degrees F at depth to 52 degrees F in the shallows.

Operators Dykkersport Trondheim A/S is close to the city center and has close links with the only live-aboard in the region, the M/S Sula ( www.liveaboard.no ) — a large, robust and comfortable dive boat that regularly makes local expeditions to explore the wrecks and reefs of Trondheim fjord.

Price Tag Norway can be a criminally expensive place to eat and drink, so a live-aboard is a good option (and Sula has the cheapest beer in town): One week aboard the Sula is $2,680 and includes food, accommodations and air fills. One dive with the Zodiac is $90, two dives is $144.