Befriending Giants

There has been a lot of controversy surrounding the recently “discovered” Oslob, Philippines whale shark situation because of the feeding of the sharks that accompanies the tourism.

As with all things in life, there are many strong opinions and diverse viewpoints.However, there is much to be learned by opening our minds to alternative perspectives, even if we don’t end up agreeing with that perspective. The saying “seek first to understand, then to be understood” comes to mind, and it was in this spirit that I approached the story of Oslob’s whale sharks.

The following discussion is based on my direct, personal observations.

Feeding of the whale sharks

The whale sharks that come to Oslob are targeting tiny shrimp that rise to the surface at night. These shrimp move in toward the shallows under moonlight. The fishermen catch small quantities of the same shrimp that the whale sharks are eating by using small lights on their canoes and very fine-mesh hand nets (in 1 meter of water).

I observed the whale sharks at night in 2-3 meters of water passing back/forth as they fed on the shrimp. It was hard to believe how shallow they were feeding! In the day, the whale sharks were still in the area, possibly waiting for the evening when the shrimp rise again to the surface.

During the day, the fishermen fed the whale sharks a small amount of shrimp caught from the previous nights catch. Each whale shark may consume a few kilos. Relating to feeding concerns, my observations are as follows:

- The shrimp that are fed to the whale sharks are not larger shrimp that have been minced, as has been mistakenly reported, but are tiny shrimp that are a natural part of the whale sharks’ diet for this precise area.

- The hand feeding appears to be a small additional supplement to what the sharks eat on their own.

- The tiny shrimp are brought ashore within an hour of catching (3am when I was there), packed into sealed plastic bags and stored on ice to keep them fresh for the few hours until they are fed to the sharks.

- While I did not study the migratory behavior of the whale sharks, it is likely that migration patterns would not be impacted because they still come to feed when the shrimp are available in this area, and leave when the shrimp are not available. The fishermen report that during full moon phases, the shrimp do not appear and the whale sharks are gone.

A reasonable concern is that the whale sharks may become habituated to small boats seek possible food handouts. Whale sharks have been known to approach boats in many locations around the world already, sometimes relating to fishing methods, rather than tourism-related feeding. It remains unclear whether or how tourism feeding has any longer term impacts, but I suspect this issue needs a further look.

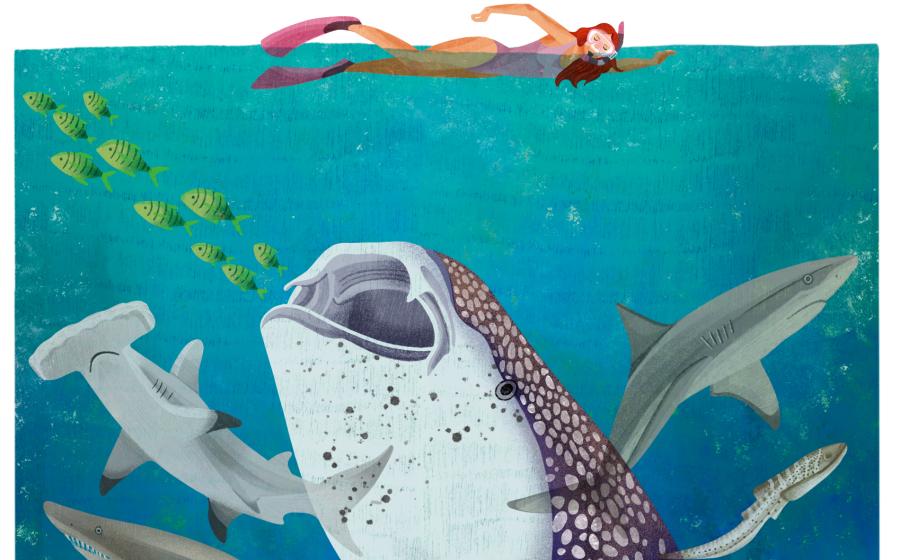

Interaction with the sharks

Another concern relates to interaction practices. I have had extensive experience visiting many whale shark diving destinations throughout the world—not just Oslob. In my experience, the greatest concerns are less about proximity of guests to whale sharks and more about density/number of tourists and also the number and actions of motorboats. I do believe there should be regulations to protect the sharks. Here are my thoughts:

- Guidelines should focus on managing the number of boats and guests at any given time in the water interacting with the sharks. In many places, the “one boat per shark” rule makes a lot of sense, with a limit of number of guests per shark.

- If motor boats are being used (they are not in Oslob), the boats should not gun their motors to approach a shark when sighted and the boat should keep sufficient distance from the shark to reduce the chance of maiming the shark with the propellers.

- Riding and handling of sharks should be prohibited. Though riding on sharks has been reported in the past at Oslob, the new regulations prohibit this.

- In the case of Oslob, the whale sharks are feeding on their natural prey but certainly not in a natural manner because they remained mostly stationary and upright. My observations were that they cared little for divers or snorkelers and even approached them without concern.

Diving with whale sharks

Another controversy is whether SCUBA diving or snorkeling is the preferred means of experiencing whale sharks. Some suggest that diving negatively affects the animals. However, there are many locations around the world, including Galapagos, Cocos, Seychelles, Maldives, Mozambique, Thailand, where diving with whale sharks is endorsed and promoted and does not seem to have any negative impact.

- Diving does raise the issue of diver safety when divers must share the open water with boat traffic and moving animals. In Oslob, however, both the whale sharks and the boats are remaining in relatively fixed positions. There is no need for divers to make rapid ascents.

- A second issue relates to the animals using the water column to create breaks from tourists. In Oslob, the animals are generally stationary at the surface and in shallow water. As such, there is no need, intention or even possibility for the animals to move way or seek space.

The new regulations in Oslob

At the time of my visit to Oslob in early December, 2011, the whale sharks were only known to a few local operators and no regulations of any type were in place. While concerning, visitor traffic was still minimal. After I completed documenting the extraordinary situation at Oslob, I requested that all members of my dive group not publicize the Oslob whale sharks until such time as I could help the implementation of proper guidelines. I was concerned that if the world found out about Oslob, the situation could spin out of control.

I submitted my findings and recommendations to the parties involved in establishing the regulations. I collaborate with many of the top marine mega-fauna researchers, and I have extensive experience dealing in the management of tourism interactions with whale sharks and manta rays in locations around the world. I also work closely with fishing communities in remote locations around the world helping them foster development of tourism opportunities (as apposed to destructive fishing).

When I landed back home in the USA, I discovered that a Philippine newspaper had just run a feature on Oslob’s whale sharks. A brief search of the internet revealed blogs and images popping up everywhere. The story was out.

In the face of what I considered to be rampant hearsay and growing speculative commentary, I made the decision to release my story to the press.

I was happy to see that my input was well received and my recommendations considered in the final regulations, as I’m sure others were. In late January (just a few weeks ago) the following regulations were implemented:

1. Whale Shark Viewing Time Opens at 6 AM and closes at 1PM

2. Rules in Watching Whale Sharks

• Do not touch, ride, or chase a whale shark

• Do not restrict normal movement or behavior of the shark

• Flash photography are not allowed

• Motorboats are prohibited in the area. Only paddleboats are allowed.

• Viewing is limited to 30 minutes

• A maximum of six tourists is allowed to view for 30 minutes while a maximum of four divers is allowed to avoid crowding.

There has been widespread criticism that the regulations, after just a few weeks, are being ignored and not properly implemented. We must bear in mind however, that these regulations have just been implemented, and that this village has very little experience with tourism management. As such, they are starting with minimal infrastructure and training is in place. It takes time, commitment and support to properly implement regulations and socialize them within communities, and for us to continue to reinforce the importance of these regulations being applied effectively.

In my opinion, the above regulations are some of the strictest in the industry with regard to whale shark interaction. In Donsol, Ningaloo, Thialand, the Maldives, parts of Mexico, and most other locations, far more tourists are allowed to interact with the whale sharks. Furthermore, in these other locations motorized boats often run intercepts on the whale sharks to drop tourists as close as possible to minimize their swimming. The consequences are self evident, as whale sharks in these areas frequent exhibit scars from propellers and chopped dorsal and tail fins. Having spent time photographing in these areas, I find it is difficult to produce an image of a whale shark that has not been injured. I wouldn’t want to stop (and in fact endorse) the whale shark diving in these areas, but instead offer these examples to help us shed a fair and honest light on the Oslob situation.

Closing Comments

Many of us in the diving and conservation community care deeply about these animals, as well as the opportunity to experience them. There are different ways and places to experience sharks. Seeing the controversy the feeding of these sharks has caused, I realize that we may all share a passion for these animals, but may still disagree on what the graver concerns may be. I’m personally disheartened that the outcry over the feeding of these sharks has been louder than that over the illegal slaughter of manta rays in this very same region.

The greatest and continuing concern remains the killing of these animals. The history in this region has been one where whale sharks have been targeted and slaughtered for fins and meat, both before and since the ban. Some villages of Bohol have systematically targeted whale sharks and largely wiped them out in waters of the region.

The fishermen in Oslob related that up until a decade ago, dozens of whale sharks were prevalent in their waters throughout the year and regularly encountered during their fishing. Fishermen then came from Bohol and slaughtered large numbers of whale sharks for their fins. Once they were done, the whale sharks were gone. Now a decade later, some have returned. While the Oslob village was not the killers, they are only now valuing these animals alive and the fishing community has a stake in the conservation of these whale sharks.

Let’s celebrate this progress while at the same time working towards proper management and interaction practices. We have an opportunity in Oslob to work with this fishing community (not against it), to help them foster more responsible interaction practices. These fishermen expressed true affection and appreciation for these animals, and are eager to develop tourism while maintaining the well being of the whale sharks. Rather than become embroiled in debate and criticism, we should be a positive force in helping that happen, because the bottom line is, the greatest threat to these animals is directed fisheries and not tourism.

There has been a lot of controversy surrounding the recently “discovered” Oslob, Philippines whale shark situation because of the feeding of the sharks that accompanies the tourism.

As with all things in life, there are many strong opinions and diverse viewpoints.However, there is much to be learned by opening our minds to alternative perspectives, even if we don’t end up agreeing with that perspective. The saying “seek first to understand, then to be understood” comes to mind, and it was in this spirit that I approached the story of Oslob’s whale sharks.

The following discussion is based on my direct, personal observations.

Feeding of the whale sharks

The whale sharks that come to Oslob are targeting tiny shrimp that rise to the surface at night. These shrimp move in toward the shallows under moonlight. The fishermen catch small quantities of the same shrimp that the whale sharks are eating by using small lights on their canoes and very fine-mesh hand nets (in 1 meter of water).

I observed the whale sharks at night in 2-3 meters of water passing back/forth as they fed on the shrimp. It was hard to believe how shallow they were feeding! In the day, the whale sharks were still in the area, possibly waiting for the evening when the shrimp rise again to the surface.

During the day, the fishermen fed the whale sharks a small amount of shrimp caught from the previous nights catch. Each whale shark may consume a few kilos. Relating to feeding concerns, my observations are as follows:

- The shrimp that are fed to the whale sharks are not larger shrimp that have been minced, as has been mistakenly reported, but are tiny shrimp that are a natural part of the whale sharks’ diet for this precise area.

- The hand feeding appears to be a small additional supplement to what the sharks eat on their own.

- The tiny shrimp are brought ashore within an hour of catching (3am when I was there), packed into sealed plastic bags and stored on ice to keep them fresh for the few hours until they are fed to the sharks.

- While I did not study the migratory behavior of the whale sharks, it is likely that migration patterns would not be impacted because they still come to feed when the shrimp are available in this area, and leave when the shrimp are not available. The fishermen report that during full moon phases, the shrimp do not appear and the whale sharks are gone.

A reasonable concern is that the whale sharks may become habituated to small boats seek possible food handouts. Whale sharks have been known to approach boats in many locations around the world already, sometimes relating to fishing methods, rather than tourism-related feeding. It remains unclear whether or how tourism feeding has any longer term impacts, but I suspect this issue needs a further look.

Interaction with the sharks

Another concern relates to interaction practices. I have had extensive experience visiting many whale shark diving destinations throughout the world—not just Oslob. In my experience, the greatest concerns are less about proximity of guests to whale sharks and more about density/number of tourists and also the number and actions of motorboats. I do believe there should be regulations to protect the sharks. Here are my thoughts:

- Guidelines should focus on managing the number of boats and guests at any given time in the water interacting with the sharks. In many places, the “one boat per shark” rule makes a lot of sense, with a limit of number of guests per shark.

- If motor boats are being used (they are not in Oslob), the boats should not gun their motors to approach a shark when sighted and the boat should keep sufficient distance from the shark to reduce the chance of maiming the shark with the propellers.

- Riding and handling of sharks should be prohibited. Though riding on sharks has been reported in the past at Oslob, the new regulations prohibit this.

- In the case of Oslob, the whale sharks are feeding on their natural prey but certainly not in a natural manner because they remained mostly stationary and upright. My observations were that they cared little for divers or snorkelers and even approached them without concern.

Diving with whale sharks

Another controversy is whether SCUBA diving or snorkeling is the preferred means of experiencing whale sharks. Some suggest that diving negatively affects the animals. However, there are many locations around the world, including Galapagos, Cocos, Seychelles, Maldives, Mozambique, Thailand, where diving with whale sharks is endorsed and promoted and does not seem to have any negative impact.

- Diving does raise the issue of diver safety when divers must share the open water with boat traffic and moving animals. In Oslob, however, both the whale sharks and the boats are remaining in relatively fixed positions. There is no need for divers to make rapid ascents.

- A second issue relates to the animals using the water column to create breaks from tourists. In Oslob, the animals are generally stationary at the surface and in shallow water. As such, there is no need, intention or even possibility for the animals to move way or seek space.

The new regulations in Oslob

At the time of my visit to Oslob in early December, 2011, the whale sharks were only known to a few local operators and no regulations of any type were in place. While concerning, visitor traffic was still minimal. After I completed documenting the extraordinary situation at Oslob, I requested that all members of my dive group not publicize the Oslob whale sharks until such time as I could help the implementation of proper guidelines. I was concerned that if the world found out about Oslob, the situation could spin out of control.

I submitted my findings and recommendations to the parties involved in establishing the regulations. I collaborate with many of the top marine mega-fauna researchers, and I have extensive experience dealing in the management of tourism interactions with whale sharks and manta rays in locations around the world. I also work closely with fishing communities in remote locations around the world helping them foster development of tourism opportunities (as apposed to destructive fishing).

When I landed back home in the USA, I discovered that a Philippine newspaper had just run a feature on Oslob’s whale sharks. A brief search of the internet revealed blogs and images popping up everywhere. The story was out.

In the face of what I considered to be rampant hearsay and growing speculative commentary, I made the decision to release my story to the press.

I was happy to see that my input was well received and my recommendations considered in the final regulations, as I’m sure others were. In late January (just a few weeks ago) the following regulations were implemented:

1. Whale Shark Viewing Time Opens at 6 AM and closes at 1PM

2. Rules in Watching Whale Sharks

• Do not touch, ride, or chase a whale shark

• Do not restrict normal movement or behavior of the shark

• Flash photography are not allowed

• Motorboats are prohibited in the area. Only paddleboats are allowed.

• Viewing is limited to 30 minutes

• A maximum of six tourists is allowed to view for 30 minutes while a maximum of four divers is allowed to avoid crowding.

There has been widespread criticism that the regulations, after just a few weeks, are being ignored and not properly implemented. We must bear in mind however, that these regulations have just been implemented, and that this village has very little experience with tourism management. As such, they are starting with minimal infrastructure and training is in place. It takes time, commitment and support to properly implement regulations and socialize them within communities, and for us to continue to reinforce the importance of these regulations being applied effectively.

In my opinion, the above regulations are some of the strictest in the industry with regard to whale shark interaction. In Donsol, Ningaloo, Thialand, the Maldives, parts of Mexico, and most other locations, far more tourists are allowed to interact with the whale sharks. Furthermore, in these other locations motorized boats often run intercepts on the whale sharks to drop tourists as close as possible to minimize their swimming. The consequences are self evident, as whale sharks in these areas frequent exhibit scars from propellers and chopped dorsal and tail fins. Having spent time photographing in these areas, I find it is difficult to produce an image of a whale shark that has not been injured. I wouldn’t want to stop (and in fact endorse) the whale shark diving in these areas, but instead offer these examples to help us shed a fair and honest light on the Oslob situation.

Closing Comments

Many of us in the diving and conservation community care deeply about these animals, as well as the opportunity to experience them. There are different ways and places to experience sharks. Seeing the controversy the feeding of these sharks has caused, I realize that we may all share a passion for these animals, but may still disagree on what the graver concerns may be. I’m personally disheartened that the outcry over the feeding of these sharks has been louder than that over the illegal slaughter of manta rays in this very same region.

The greatest and continuing concern remains the killing of these animals. The history in this region has been one where whale sharks have been targeted and slaughtered for fins and meat, both before and since the ban. Some villages of Bohol have systematically targeted whale sharks and largely wiped them out in waters of the region.

The fishermen in Oslob related that up until a decade ago, dozens of whale sharks were prevalent in their waters throughout the year and regularly encountered during their fishing. Fishermen then came from Bohol and slaughtered large numbers of whale sharks for their fins. Once they were done, the whale sharks were gone. Now a decade later, some have returned. While the Oslob village was not the killers, they are only now valuing these animals alive and the fishing community has a stake in the conservation of these whale sharks.

Let’s celebrate this progress while at the same time working towards proper management and interaction practices. We have an opportunity in Oslob to work with this fishing community (not against it), to help them foster more responsible interaction practices. These fishermen expressed true affection and appreciation for these animals, and are eager to develop tourism while maintaining the well being of the whale sharks. Rather than become embroiled in debate and criticism, we should be a positive force in helping that happen, because the bottom line is, the greatest threat to these animals is directed fisheries and not tourism.